CROWN.

A research project on the materiality, technology and state of preservation of the Imperial Crown in Vienna.

About the project

From 2022 to 2024, interested persons were able to use this website to access information about our research project on the Imperial crown in Vienna, find out more about research interests and methods, to stay abreast of research developments and first findings. This site also listed and thanked the many institutions and persons without whose support (in terms of funding, organization, and/or concept) this interdisciplinary project could not have been realized.

In total, images of and data on about 1,750 individual components of the crown were compiled, making a collection of around 43,000 data sets. In addition, there are reference images and data from nineteen further goldsmitheries in Vienna, Essen, Munich, and Cologne as well as mappings, technical drawings, and 3D visualizations made specifically for this purpose.

During the final months of the project period, our work and our communication with international experts was focussed entirely on tapping and evaluating this extensive material. One thing emerged first and foremost as a certainty and point of agreement: that many of the facts that have now, in this form and to this extent, been inferred for the first time raise a number of new questions without fast and easy answers. The same applies to a matter that continues to be controversially discussed among art historians and historians: not even direct exchange made it possible to agree on when to date the object to.

It is all the more important to process and publish the collected data to provide a basis for further research. Thanks to funding made available by the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung, the Swiss Fondation Etrillard as well as private sponsors, further work will be possible in 2025 to prepare a book publication as well as making selected research data available in an open access format.

Unfortunately, the information provided on the project by this website cannot be complete. The sheer extent and complexity of all questions and methods, observations and findings that were compiled between 2022 and 2024 cannot be done full justice and explained in this setting. That calls for the scholastic formats mentioned above, which are currently in progress and which can serve as starting points for further research. The section ‘What do we know?’, which was written for this website at the start of the project, has therefore also not been altered. We merely corrected or added some facts and numbers.

Why research the Imperial Crown in Vienna?

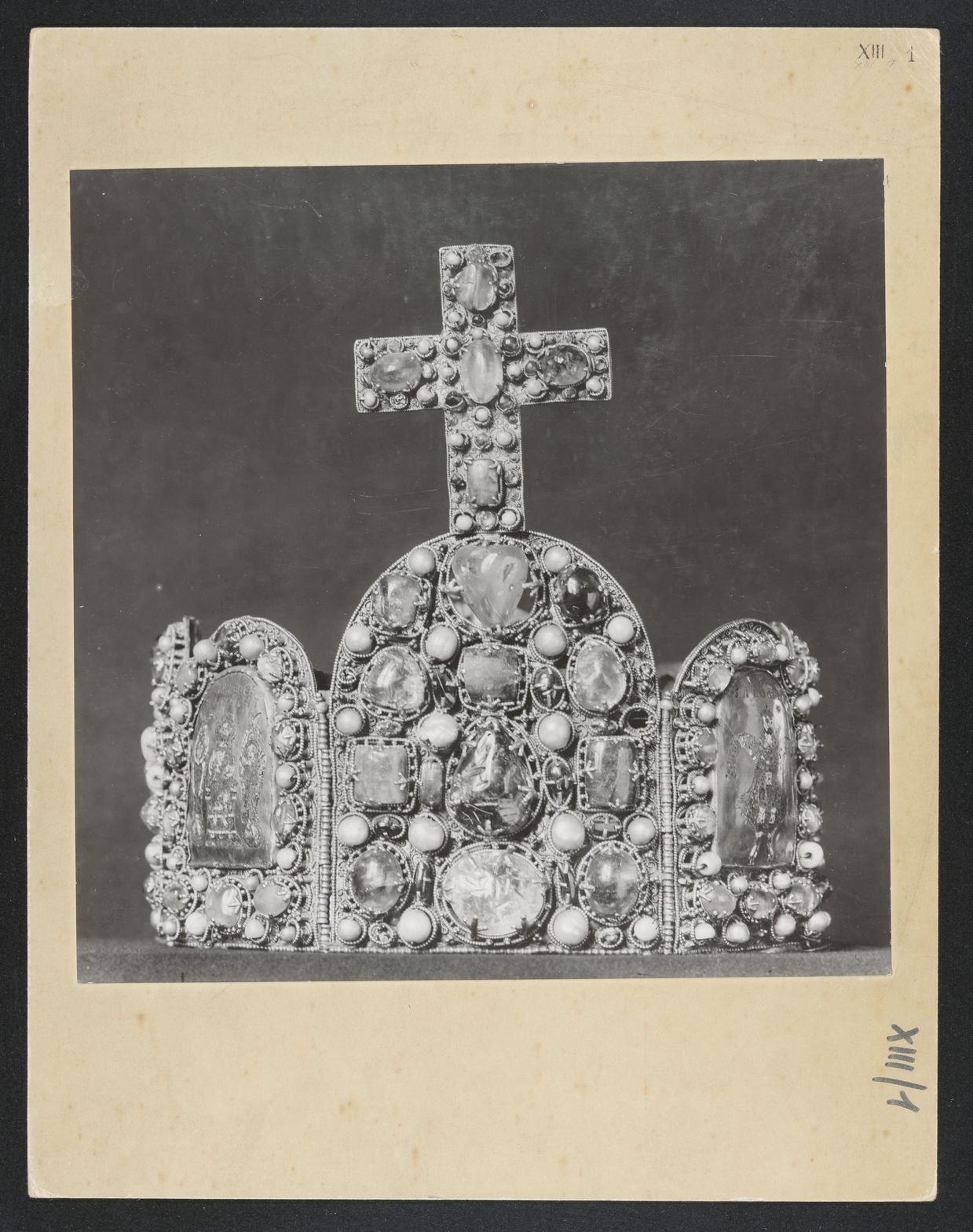

Its legendary association with Charlemagne (r. 768–814) ensured both that the Imperial Crown now in Vienna was venerated as a sacred relic of this canonized ruler and its status as an insignia of the Holy Roman Empire (of the German Nation). The crown remained in use until the last coronation in 1792, embedding itself in our collective memory as one of the most important and evocative symbols of European history.

This continued use directly relates to its survival. Today, it is the only one of numerous crowns owned and used by kings and emperors in the Middle Ages to have survived.

At the same time, this use has resulted in numerous losses, additions, damages, and repairs. Until now, research had primarily addressed historical and art historical issues and only in rare cases touched on these interventions and the object’s actual condition. CROWN, by contrast, used these aspects as the very starting point for working on the crown. A particular focus was placed on ageing-related changes that reveal themselves in the condition and appearance of the crown, especially the enamel panels.

Comprehensive material-science and conservation examinations were undertaken in order to better understand the fundamental processes, their origins and effects, and the crown itself. They also served to establish the best possible protection for preserving the crown into the future.

These examinations were the focus of this research project as of 1 January 2022. For the very first time, this interdisciplinary project comprehensively analyzed and documented material compositions, techniques, interventions, and alterations. Examination results of selected comparative examples, which were also analyzed, were used to further interpret these findings. The systematic collection of textual and visual sources was intended to expand our knowledge of the artefact’s ’fate’, especially for the period after 1500, and to help us to identify approaches to better understand early-modern interventions and alterations.

A close look was also taken at all the inscriptions on the crown. It was the first time that technological and epigrammatic findings were gathered and debated with a particular view to the issue of dating the object in direct interdisciplinary exchange.

Who made this project possible?

In the first place, we would like to thank the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and the Rudolf August Oetker-Stiftung for their generous support, which allowed us to initiate the project and begin work in 2022.

Additional financial means have been provided by the Austrian Ministry for the Arts and Culture (Bundesministerium for Kunst, Kultur, öffentlicher Dienst und Sport) and the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), as part of its DOC Fellowship Programme.

We would like to cordially thank these institutions as well as the numerous individual donors who have crowdfunded the project.

The project was also significantly supported by institutions and collections that provided access to objects under their care for important comparative measurements and examinations on site, that shared existing findings of their own research with the project team and/or contributed with their own resources, knowledge, and know-how:

- Berlin, Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Dr. Stefan Röhrs, Dr. Cristina Aibéo

- Essen, Domschatz Essen, Andrea Wegener MA

- Köln, Erzbistum Köln, Dr. Anna Pawlik

- Köln, Kath. Kirchengemeinde St. Severin, Dr. Joachim Oepen

- München, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, GD Dr. Frank Matthias Kammel, Dipl.-Rest. Joachim Kreutner, Dipl.-Rest. Hans-Jörg Ranz, Dr. Matthias Weniger

- München, Schatzkammer der Residenz München, Dr. Christian Quaeitzsch, Dipl.-Rest. Jonas Jückstock

- München Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Institut für Bestandserhaltung und Restaurierung (IBR), Dr. Irmhild Ceynowa, Dr. Thorsten Allscher

- Nürnberg, Staatsarchiv Nürnberg, Dr. Daniel Burger

- Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des objets d’art, Florian Meunier

- Paris, Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF), Marie Godet, Ina Reiche

- Ulm, WITec Wissenschaftliche Instrumente und Technologie GmbH, Dr. Miriam Boehmler, Dr. Thomas Olschewski

- Wien, Institut für Mineralogie und Kristallographie der Universität Wien, Prof. Dr. Lutz Nasdala

- Wien, Naturhistorisches Museum, GD Dr. Katrin Vohland

In addition, the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna would like to thank all donors who have so generously supported the research project on the Imperial Crown.

Research Questions & Approaches

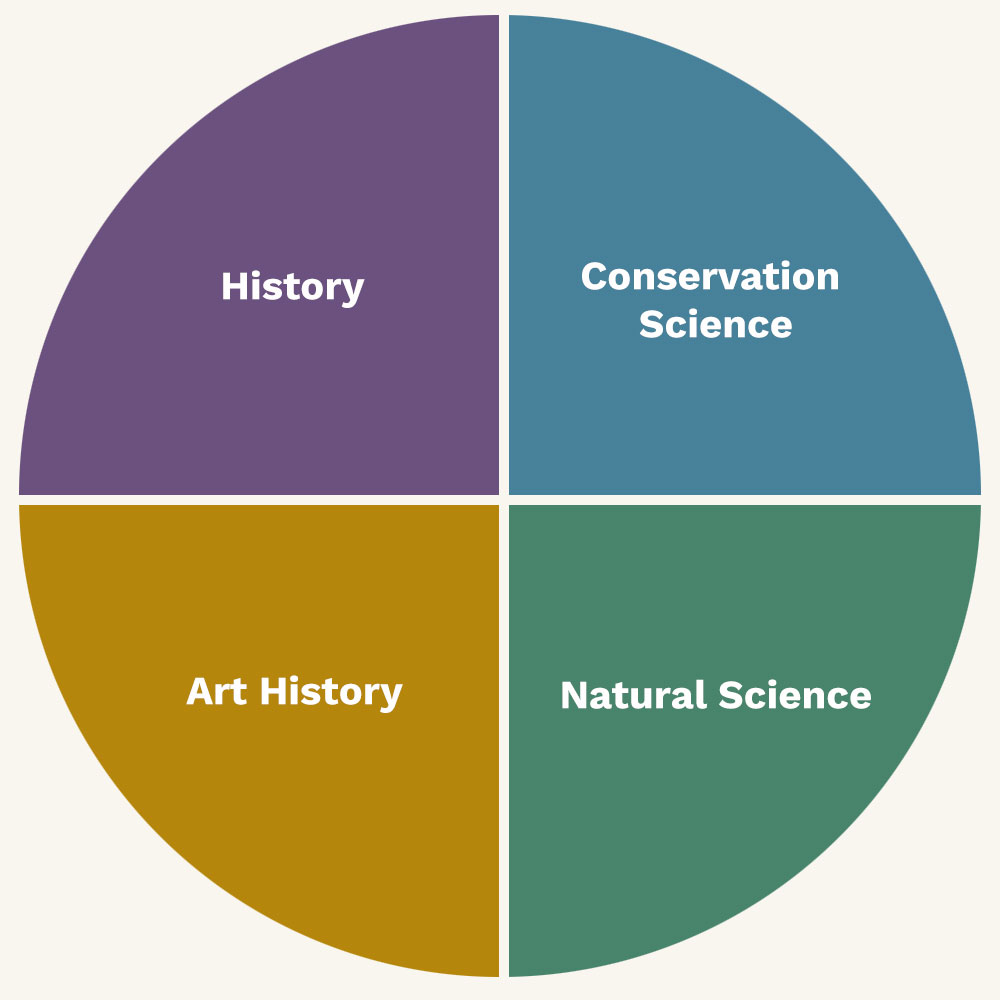

Our inter-disciplinary approach, the collaboration of historical and art-historical experts, conservators and scientists brought with it a wide variety of methods and approaches.

The continuous exchange with international experts also ensured that the pre-defined range of methods was subsequently regularly challenged, adapted when necessary, and expanded where possible.

One decisive factor for the choice of examination methods was that they had to be non-invasive. Hence, a method as obvious as that of computer tomography (CT) had to be excluded from the outset for components with gemstone and pearl applications, as the high radiation energy that is employed could have resulted in discolouration of the precious stones. It was therefore only used to examine the gold band on the crucifix above the forehead and the leather case. We were able to use a µ-CT device belonging to the Natural History Museum Vienna for that purpose.

The following information about particular examinations and observations was made available over the course of the project.

Material Analysis

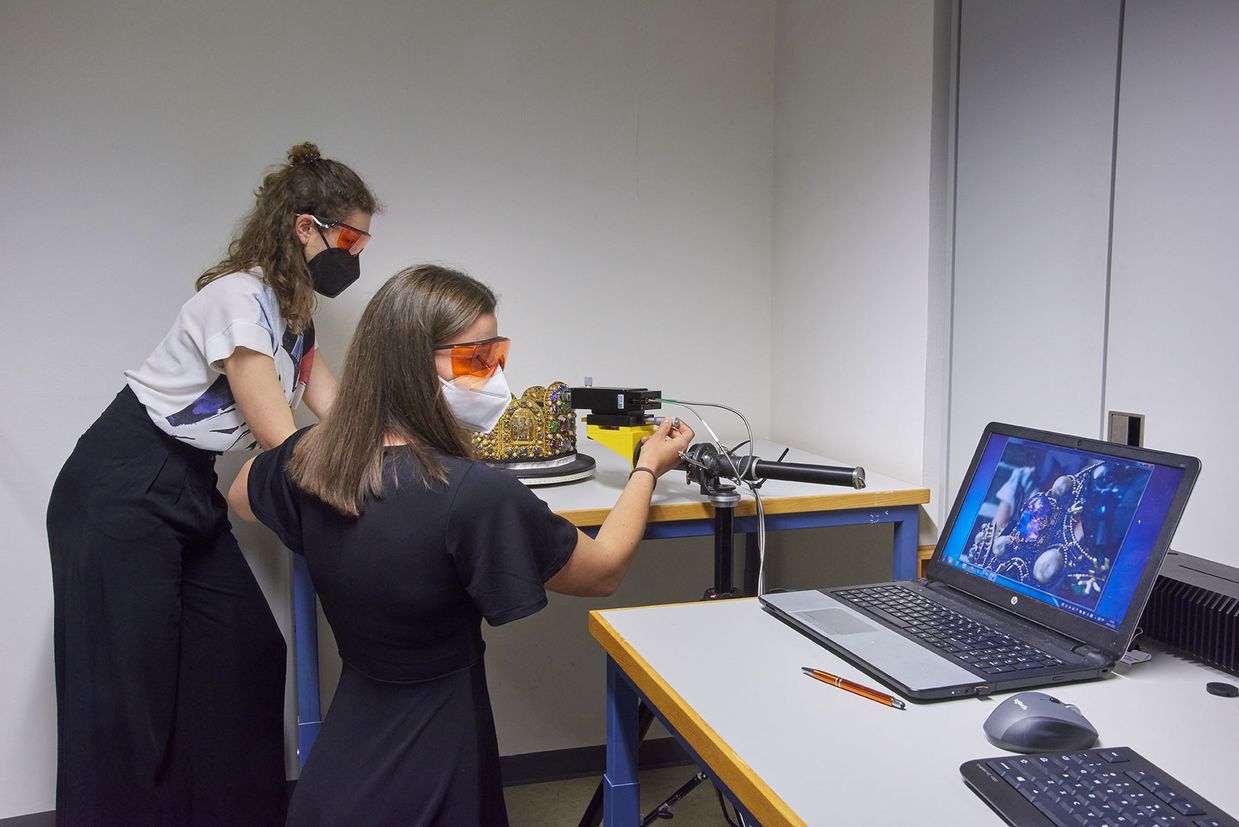

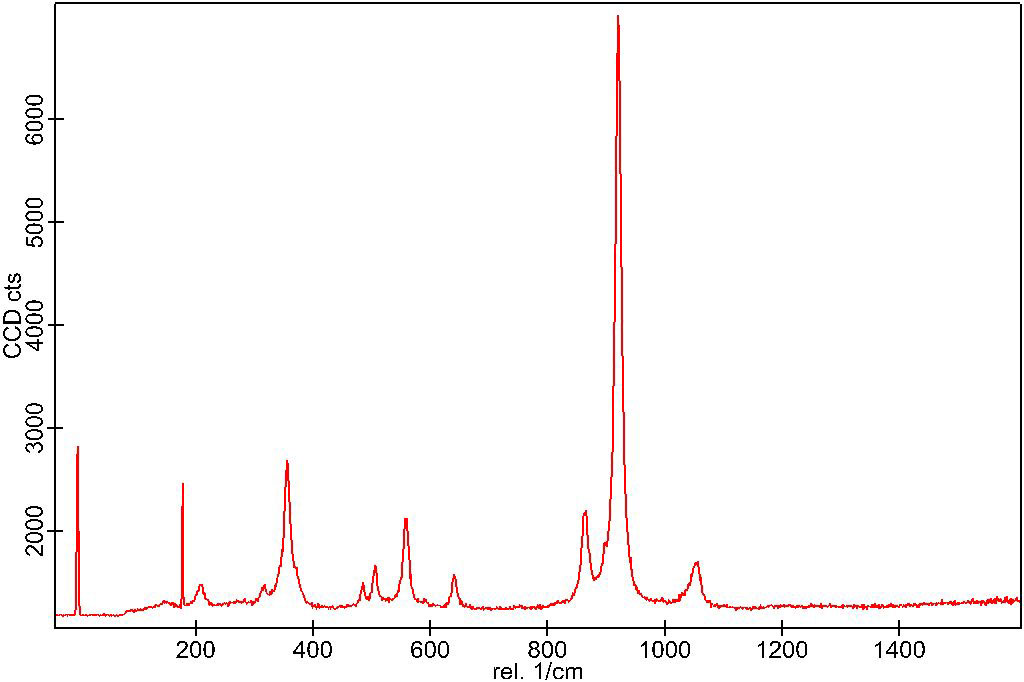

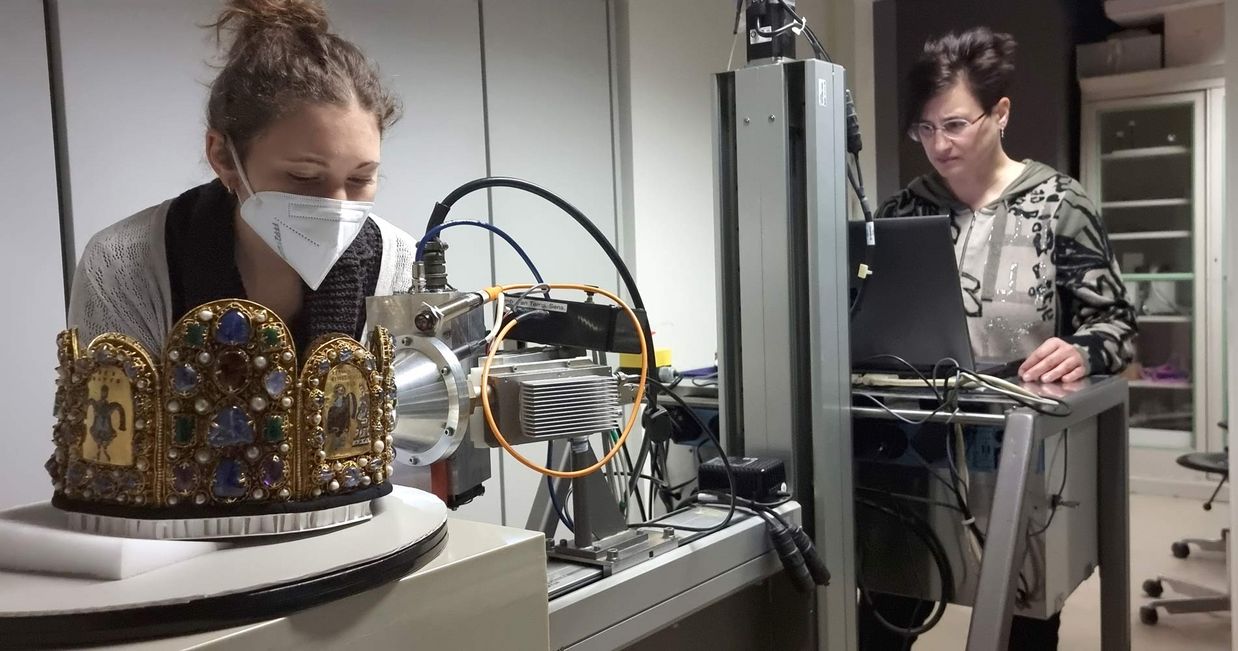

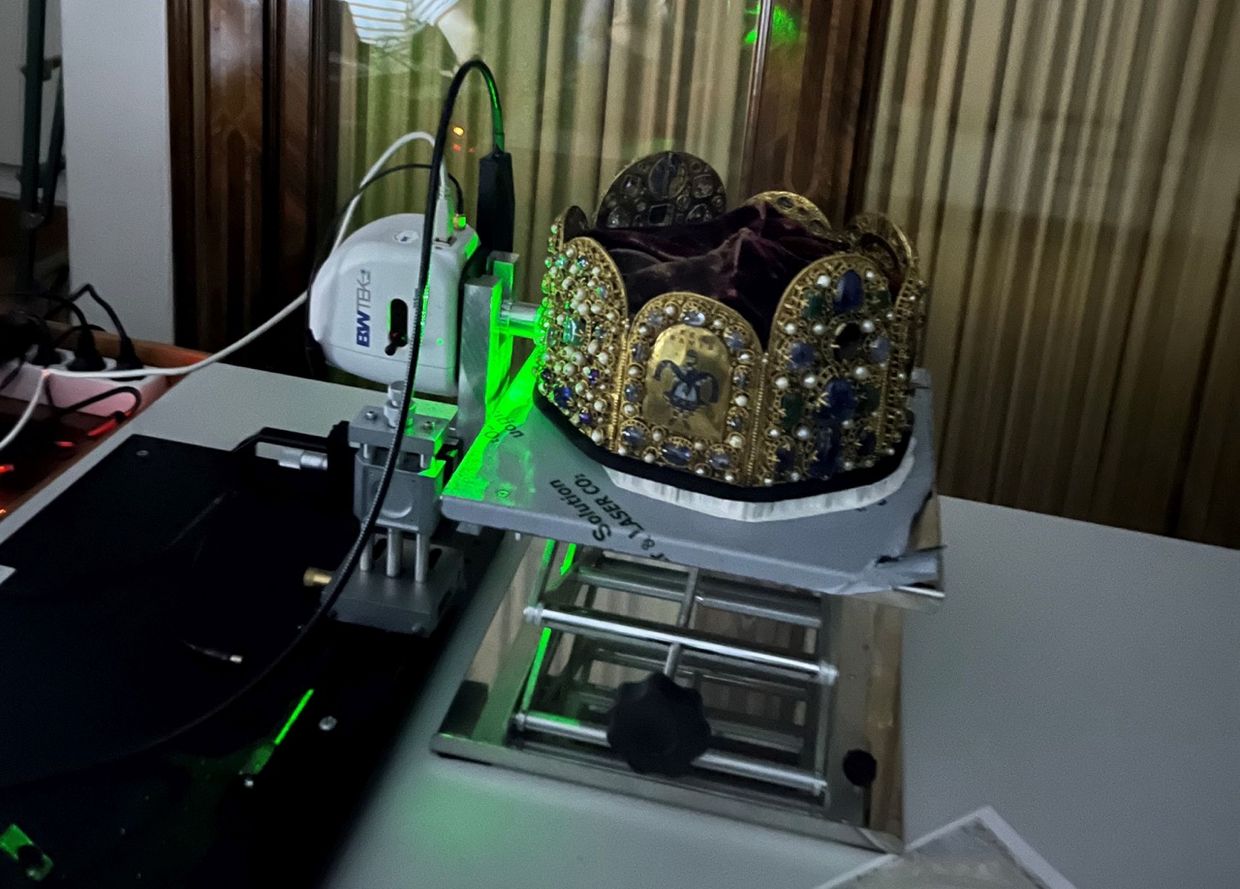

Identification of the gemstones using raman and photoluminescence spectroscopy

Identification of the gemstones using raman and photoluminescence spectroscopy

In the course of a two-week campaign to perform Raman investigations in May 2022, we systematically analysed all the gemstones adorning the imperial crown for the first time. This was undertaken in collaboration with the Institute of Mineralogy and Crystallography of the University of Vienna. Until then, all the information we had for the 172 gemstones on circlet, cross and arch were handwritten notes from 1977 recording the optical classification of some of them.

WITec Wissenschaftliche Instrumente und Technologie GmbH, a private company specializing in scientific instruments, provided us with a specially-adapted Raman spectrometer that allowed us to measure both Raman and photo-luminescence spectra. Thanks to many years of experience in determining Raman in gemstones, Professor Dr Lutz Nasdala was able to identify all the stones on the crown directly while performing the measurements.

Today, the Imperial Crown is embellished with a total of 71 sapphires, 50 garnets, 20 emeralds, 13 amethysts, four chalcedonies, three spinels, and eleven differently coloured pieces of glass. Further examinations to identify the stones in more detail are planned within the course of the project. For instance, we aim to classify different types of garnets, determine special inclusion phases, and obtain information on the origins or provenance of individual stones. We will continue to only use non-destructive examination methods such as X-ray fluorescence analysis.

Martina Griesser, 4.9.2022

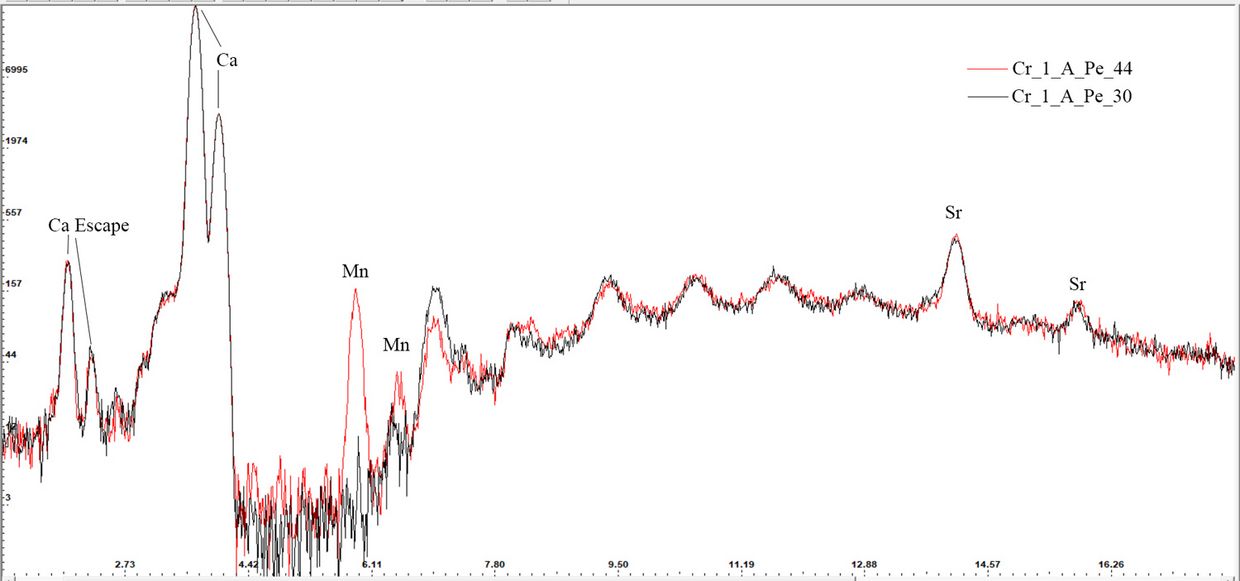

Identification of saltwater and freshwater pearls

Identification of saltwater and freshwater pearls

Today, circlet, arch and cross are decorated with a total of 233 pearls. In addition, there are about 600 smaller pearls arranged to form the letters on the arch. Pearls - also classified as organic gemstones - are a material that, like mother-of-pearl, is produced within certain types of molluscs by biomineralization processes. Thin layers of calcium carbonate crystals (aragonite, calcite or vaterite) are built up over an organic cell nucleus, creating a characteristic terrace-like structure that is responsible for the special lustre effects of pearls. Dr. Stefanos Karampelas from the Laboratoire Français de Gemmologie (LFG) Paris, an internationally renowned expert, kindly agreed to examine the pearls on the Imperial Crown.

The research project aims to describe each pearl and determine whether it is a saltwater or a freshwater pearl. This is made possible by material analytical investigations using X-ray fluorescence analysis (µ-XRF, device: PART II). The main difference in the chemical composition of saltwater and freshwater pearls is the ratio between strontium and manganese. Other characteristics are size, shape and lustre.

Initial results show that the majority of pearls used on the crown are saltwater pearls. In classical antiquity and the Middle Ages, they mainly originated in the Persian Gulf and came to Europe via various trade routes. Some of the pearls on the Imperial Crown are exceptionally large (circa 8-12 mm); they are among the largest specimens known in Europe before the discovery of America, and must have been extremely rare and costly.

Unlike gemstones, pearls are delicate and easily damaged, fractured or affected by other aging processes. Many of the pearls were (re-)attached with wires during later repair work on the settings. We may therefore assume that not all the extant pearls can be traced back to the time the crown was created. Based on the findings of optical examinations, we hope to determine which pearls are original and which are later replacements.

Teresa Lamers (24 July 2023)

Conservation-science goals and perspectives

In addition to the inhomogeneous colour distribution, the enforcement of the surface with semicircular holes created in the manufacturing process is evident. These were filled (possibly during later measures) with a wax-like mass. Also visible are the signs of corrosion in the area of the black enamel in the form of white, crystalline efflorescence.

Conservation-science goals and perspectives

The second research campaign (9 January - 23 June 2023) focused on analysing the chemical composition of the different materials that make up the Imperial Crown. Precise knowledge of the chemical composition is an essential basis of conservation science research. It enables conclusions to be drawn about specific material properties and about ageing and corrosion processes. Likewise, the results of analyses can provide clues to the origin (as in the case of precious stones) or be used to determine the species (as in the case of pearls).

[link: Material Analysis / Examination of the pearls]

However, the analysis possibilities are limited by the mandatory requirement of non-destruction (no sampling) and mobility (equipment must be transported to the crown - not vice versa). The three-dimensional structure, especially of the gold surfaces, is a further, strongly limiting factor in the investigations. The relatively large measuring heads of the analysers have to be brought very close to the surface. This is only possible at isolated points on the crown, which limits a complete and systematic examination of the gold alloys from the outset. The enamels, with their only slightly curved flat surfaces, offer better measuring conditions.

By using different, complementary optical and material-analytical examination methods, we are trying to obtain as broad a spectrum of information as possible in order to deepen our knowledge of the materiality, the state of preservation and the complex corrosion processes.

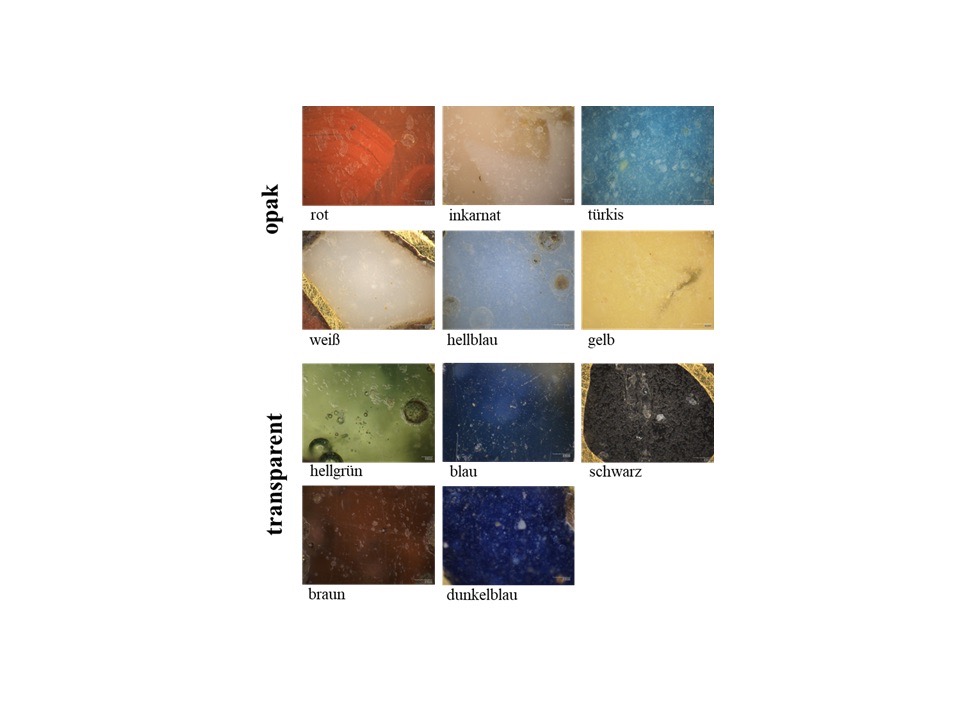

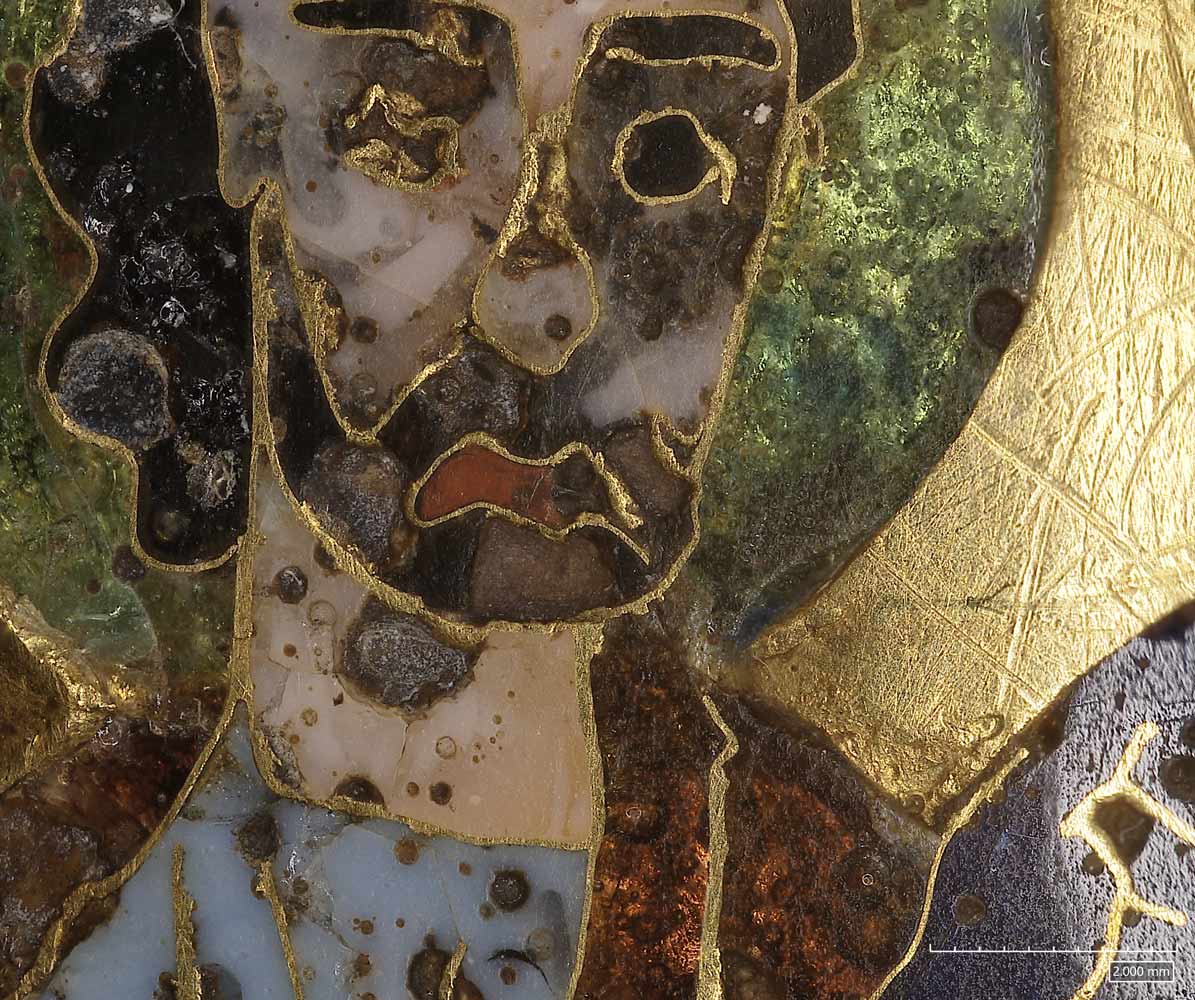

Within the project, the enamels of the Imperial Crown represent a main topic of conservation science. Enamel is not a stable system. It is particularly subject to chemical or physical processes that take place on a micromolecular level within the enamel layers and become visible over time as signs of decay. Changes in appearance in the form of white, crystalline efflorescence were also observed on the sinking enamels of the Imperial Crown. A particular feature of the enamels of the Imperial Crown is the strong inhomogeneity of individual colours as well as the enforcement of the surfaces with a multitude of semicircular holes that were created during the manufacturing process (trapped gas bubbles that migrated to the surface during the melting of the enamel in the kiln). Point measurements cannot adequately characterise the chemical composition in this case. However, with the macro X-ray fluorescence scanner it is possible to record spectra from the entire surface, map and display the elemental distribution.

[link: Material Analyses / Further material analyses using the macro-XRF scanner CRONO]

The great challenge for conservation science will be to interpret the results obtained from the measurement data to understand what they mean for the corrosion processes, what conservation measures need to be taken and what consequences need to be drawn in terms of optimising the storage conditions to ensure the long-term preservation of the crown.

Helene Hanzer (20. 7. 2023)

Analyses of gold, enamel, gemstones, and pearls using µ-X-ray fluorescence analysis

Analyses of gold, enamel, gemstones, and pearls using µ-X-ray fluorescence analysis

The portable X-ray fluorescence device PART II, already used for the analysis of niello [link: Material Analysis / Analysis of the Niello Decoration], was used in spring 2023 to investigate the chemical composition of gemstones, pearls and enamels of the Imperial Crown as well as the gold composition due to its small measuring spot of only about 150 µm. Of particular importance for enamel analysis is that the measuring head of this instrument can be evacuated. This allows the detection of light elements with low atomic numbers - such as sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg) and aluminium (Al) - which are essential for the determination of enamel composition. At the same time, however, the small working distance of only 1 mm is often a hindrance due to the strongly three-dimensional structure of the imperial crown, and therefore not all details to be investigated are always accessible with this device. Despite this limitation, it was possible to carry out a large number of analyses, in the interpretation of which it was possible to include preliminary investigations that had already been carried out in 2014, as they formed a valuable basis for the further investigations.

In addition to areas representative of the different coloured enamels, areas attacked by corrosion or those with unclear characteristics were also analysed. Overall, the following observations were made, although the complete evaluations will still take some time:

- Most enamel colours (green, light blue, dark blue, turquoise blue and brown-red) are of the soda-lime type. The incarnate and the yellow enamel are basically also of the soda-lime glass type, but in contrast to the aforementioned colours, they have clear additions of lead oxide (PbO). The enamel of the potassium glass type includes black and brick-red enamel. The K2O content of these glasses is approx. 10 and 16 percent by weight respectively. The CaO content (stabiliser in the glass) is very high and lies at 12-15 percent by weight. Nevertheless, the black enamel proves to be very unstable and shows the most conspicuous signs of corrosion. Initial analyses of the corrosion products with the scanning electron microscope (SEM) showed the presence of calcium, sodium, potassium and lead compounds (chlorides and probably carbonates or salts of organic acids). Further investigations into corrosion and its cause using µ-raman spectroscopy and SEM are planned. For enamelling technology, it is of interest here that potash glasses have a higher melting point than soda-lime glasses.

- For the pearls at the crown and cross and the large pearls of the bow, a differentiation between freshwater and saltwater pearls can be made well with XRF by comparison to reference materials based on characteristic detected elements and their relationship to each other.

[link: Material Analysis / Examination of the pearls]. - The investigation of the gold compositions was unfortunately limited by the severely restricted accessibility to the areas of interest. Nevertheless, it will be attempted to make comparisons of the individual gold alloys as far as possible and to determine technological correlations between different structural elements and alloy compositions. The comprehensive evaluations required for this are currently still in progress.

- An imitation gemstone examined on the temple shows a high barium content. Glasses of this type were first produced in the early 19th century, so the XRF analysis greatly limits the time span for the replacement of the original stone with the imitation at this point.

- The gemstones accessible for analysis were also examined in order to obtain further clues as to their exact classification and provenance or to substantiate assumptions in this regard.

For a comprehensive interpretation of pearls, gemstones and enamels, further investigations with various spectroscopic and photographic methods are planned.

Katharina Uhlir, Martina Griesser (24.7.2023)

Analyses of the niello decorations using µ-raman spectroscopy

Analyses of the niello decorations using µ-raman spectroscopy

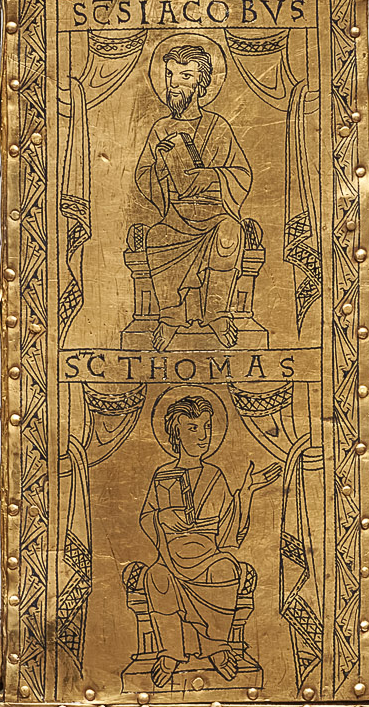

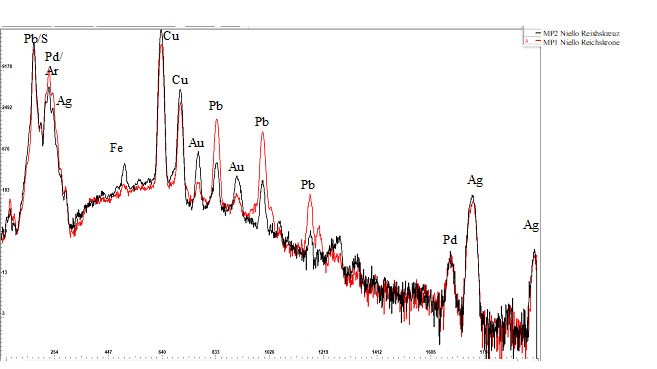

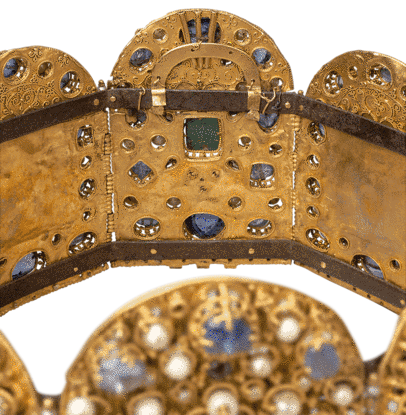

On the reverse of the Imperial Crown’s central cross, niello was melted into the engravings of Christ on the Cross and the accompanying inscriptions, delineating them more clearly against the gold background. Niello is a black-coloured mixture of sulphur and other metals. Early medieval sources report recipes containing the sulphides of silver, copper and lead as main components in various compositions.

Art historical research has repeatedly linked the central cross’s image of Christ with niello decorations on the reverse of the so-called Imperial Cross (Secular Treasury, Inv. WS XIII 21). This examination thus aimed to determine whether such a connection could be confirmed with regard to the chemical composition of the respective niello decorations using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF). We used a portable device (PART II) that was developed and built at the KHM in the course of a previous research project ("Portable Art Analyzer - PART", project no. L430-N19, funded by the FWF). It allows focusing on the niello’s very fine lines due to its measuring spot of about 150µm.

The results of this analysis show that the niello masses of the crown’s central cross are composed of silver-, copper- and lead-sulphides as well as possibly a small trace of gold, which could come from the silver. In contrast, the niello on the Imperial Cross consists only of silver- and copper-sulphides. Only traces of lead and gold are detectable here, probably due to material impurities. At least from the perspective of the material sciences, such different formulations do not immediately corroborate a direct workshop connection between the two works.

In the further course of the project, we will continue to evaluate this data, qualifying and contextualising it with literature on the making and composition of niello in the Early and High Middle Ages. Moreover, the close examination of the goldsmith’s technique and tool marks on the crown`s central cross, made possible at an unprecedented level by the use of 3D-digital microscopy, might also provide further insight.

Katharina Uhlir, Teresa Lamers (October 18, 2022)

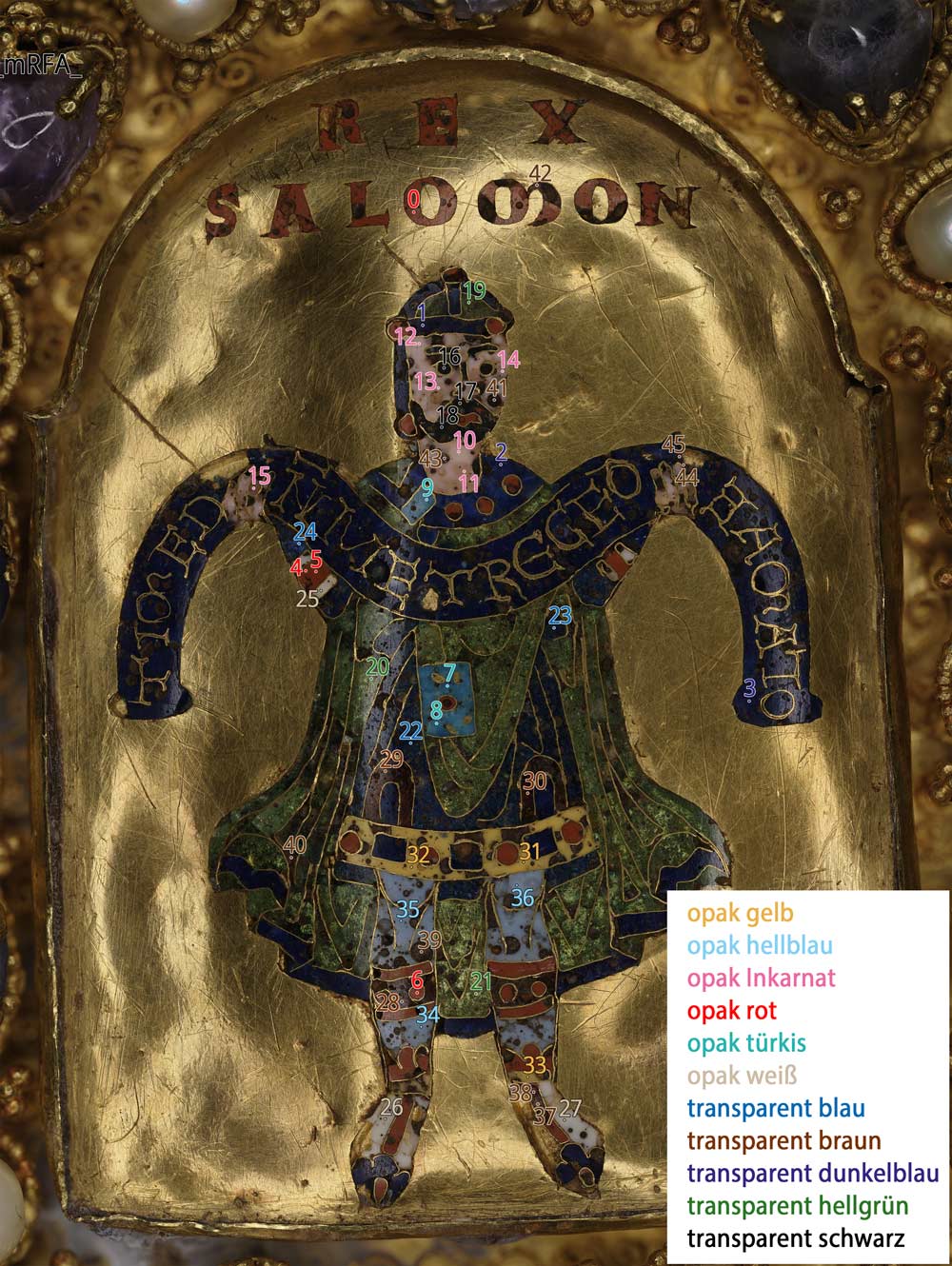

Further enamel analyses using the the macro-XRF scanner (CRONO)

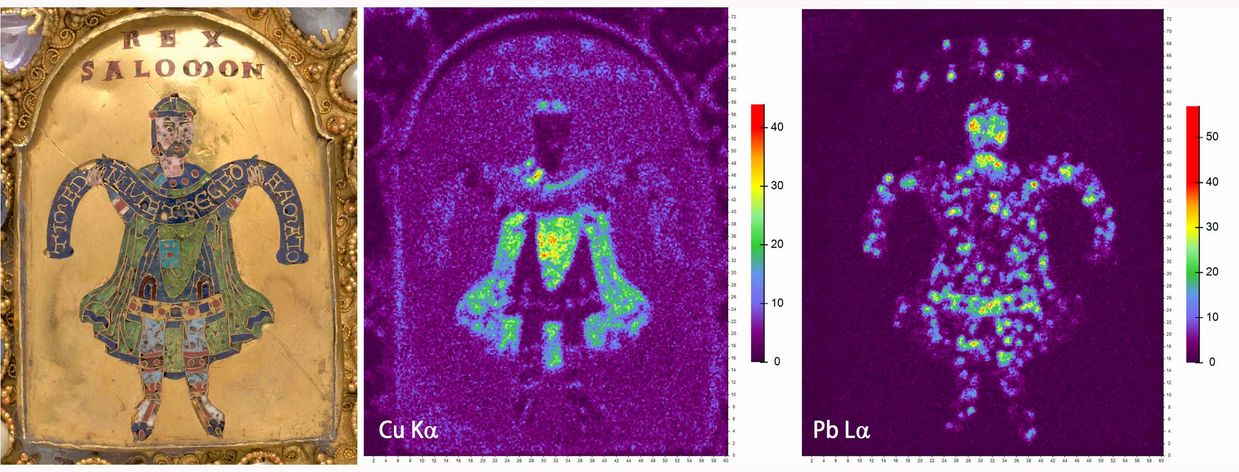

Cu Kα distribution: Enamels with copper components as colouring additives (from the highest copper content to the lowest): opaque turquoise - transparent light green - transparent dark blue - opaque red - transparent blue.

Pb Lα distribution: lead-rich enamels: opaque incarnate and opaque yellow; rest: lead-rich compound.

Further enamel analyses using the the macro-XRF scanner (CRONO)

The Kunsthistorisches Museum’s Conservation Science Department owns a Bruker CRONO macro-XRF scanner. A macro-X-ray fluorescence scanner (MA-XRF) carefully maps larger surface areas ‘pixel by pixel’ (max. 60 x 45 cm), taking an X-ray fluorescence spectrum for each data point. Together these spectra reveal key compositional information, including, for instance, the distribution of copper on the analyzed surface – on the enamel plates of the Imperial Crown it is present in blue, turquoise, green and red enamels.

In addition, the Bruker CRONO allows us to perform individual measurements at selected data points, similar to the PART II system described earlier [link: Material Analysis / Examination by means of µ-X-ray fluorescence analysis]. The collimator options are 0.5 mm, 1 mm, and 2 mm diameter, providing elemental data from a much larger data-point than that using a µ-XRF. Compared to the µ-XRF system PART II, the CRONO scanner can take measurements from a greater distance (1 cm), facilitating the mapping of data points on three-dimensional objects. At the same time, however, aerial absorption of signals from elements with a low atomic number (esp. sodium, magnesium, phosphorus, and aluminum) is especially problematic when analyzing enamel.

In May and June 2023, the following analyses were carried out, but their comprehensive interpretation will require some time:

- mapping of the enamel pates: despite the enamel plates’ convex shape, the distribution of the characteristic elements responsible for color in the different enamels is clearly represented; we were able to document the distribution of a not-yet-identified dark leaded substance

- small areas of the cross were scanned in order to define the individual zones of the different metal alloys at the solder joints. A scan of the niello decoration revealed inhomogeneities and varying thicknesses of the different layers

- high-resolution scans of both sides of the arch were an attempt to determine whether the countless tiny pearls are freshwater or saltwater pearls; however, the procedure proved unsuitable

- in addition to our earlier analyses using the PART II system, some of the gold areas were analyzed using the CRONO’s point measurement mode. Despite the much-improved access to several data points, a number of interesting points could still not be investigated regardless of the increased distance between the XRF system and object

- the metal components of the case were analyzed to determine the comparability of its individual parts

- as preparation for comparative measurements of objects in Germany (Cologne, Essen, Munich) point measurements of the enamel on the Imperial Crown were carried out using parameters determined in collaboration with the Rathgen-Forschungslabor, in order to optimize the comparability of results of investigations undertaken with different measuring devices (CRONO MA-XRF scanner in Vienna, and ELIO scanner in Germany)

Katharina Uhlir, Martina Griesser (24 July 2023)

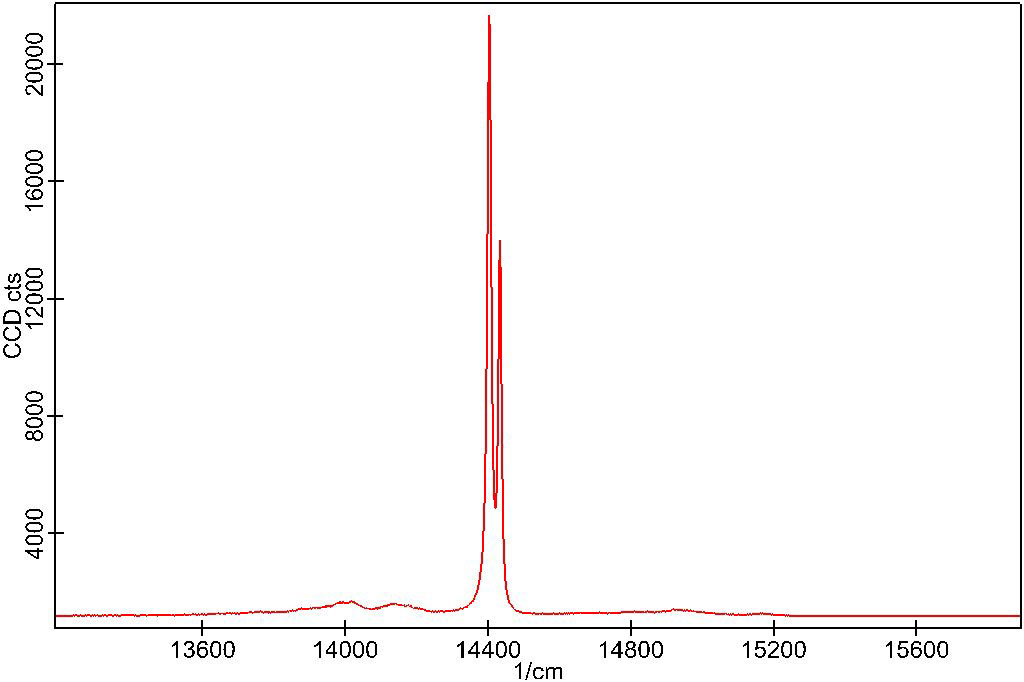

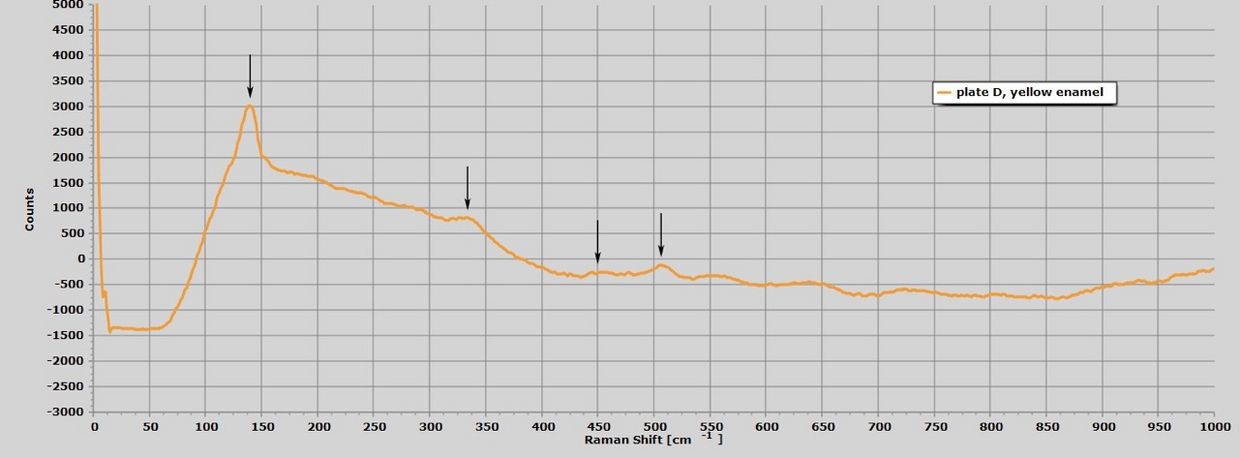

Enamel analyses using FORS and µ-Raman spectroscopy

Enamel analyses using FORS and µ-Raman spectroscopy

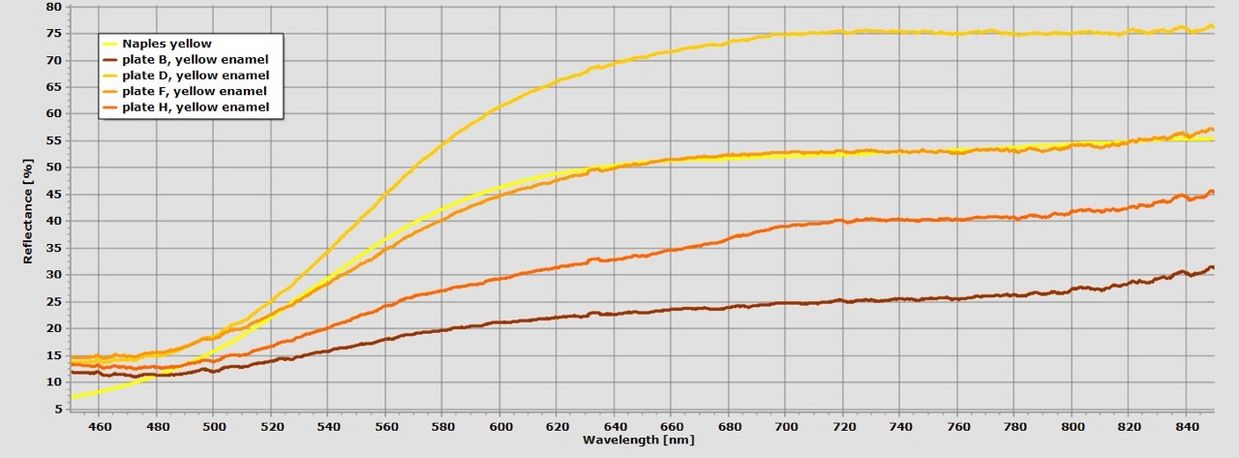

As a supplement to the studies that have already been carried out using X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF) on the differently colored enamels of the Imperial Crown , further investigations were carried out using Fibre Optics Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS) and µ-Raman spectroscopy.

FORS enables direct comparison between the opaque (white, flesh tone, yellow, red, turquoise and light blue) and the (semi-)transparent (light green, blue, dark blue, brown and black) enamel colors by recording reflection spectra when irradiated with white light. The µ-Raman spectroscopy is intended to provide further information on the chemical composition, i.e. the glass matrix used, the coloring additives for achieving the various colors and the opacifiers added to the opaque enamels. The information obtained by means of XRF analysis should be verified and, if possible, further refined with the help of these additional investigations. In addition to gaining new insights into the materials used for the Imperial Crown, the aim of the investigations is to interpret the analysis data with regard to its temporal and local classification. The possibilities and limitations for evaluating the data obtained for the Imperial Crown and comparable medieval enamelled objects are currently being developed in close cooperation with international experts.

FORS, carried out with the mobile Gorgias reflectance spectrometer from Cultural Heritage Science Open Source (CHSOS, https://chsopensource.org/reflectance-spectroscopy-system/), revealed matching spectra for all eleven enamel colors when comparing the four panels with each other. However, the color spectrum of later additions in green enamel, which can be seen on the Maiestas plate (plate H), shows clear differences. By comparing the FORS measurement results with reference spectra of known materials, it is possible to identify the coloring components of the enamel. For example, Naples yellow can be assumed to be the coloring and simultaneously opacifying component in the yellow enamel.

Raman spectroscopy enables further characterization of the chemical composition and thus – as in the case of the Naples yellow example just mentioned – clear material identification. Due to the fineness of the figurative representations in cloisonné enamel, a high lateral resolution, i.e. a µ-Raman spectrometer, is required in addition to a mobile device with a flexible positioning system in order to carry out the analyses.

As part of the EU research program Iperion HS (https://www.iperionhs.eu/), access to a suitable device was made possible via a corresponding research application (ICARE project) to MOLAB (service for mobile analysis devices). Using the portable spectrometer i-Raman Plus (BWTEC) with a multilaser source (wavelengths 532 and 785 nm), Brenda Doherty and David Buti, CNR-SCITEC (Istituto di Scienze e Tecnologie Chimiche), Perugia, carried out the Raman measurements in Vienna from October 3-5, 2023, supported by the CROWN project team.

By coupling the system to a microprobe with different lenses, the required small measuring spot size of 15-50 µm could be achieved and the measurement positioning visualized using a camera. For the total of eleven enamel colors, the most homogeneous areas possible were selected on each of the four enamel panels and measured at least twice. This allowed a total of 140 spectra to be recorded.

Initial evaluations of the µ-Raman analyses largely confirmed the results already obtained using XRF and FORS: Alkali or alkaline-earth alkali glasses were mainly used as the base glass. The type of coloring additives was also largely confirmed: the yellow was achieved by adding Naples yellow; in the turquoise, green and blue, iron oxide is partly responsible for the coloring (the cobalt used for the basic coloring of the blue enamel shows no specific Raman bands and therefore cannot be detected with this method), while the brown is due to the use of iron and manganese oxides. The addition of calcium antimonate as an opacifier in the opaque enamel colors (except for red and yellow), which was already evident from the XRF analyses, was also clearly confirmed with the help of Raman analysis.

Sabine Stanek, Martina Griesser, Teresa Lamers (23. 5. 2024)

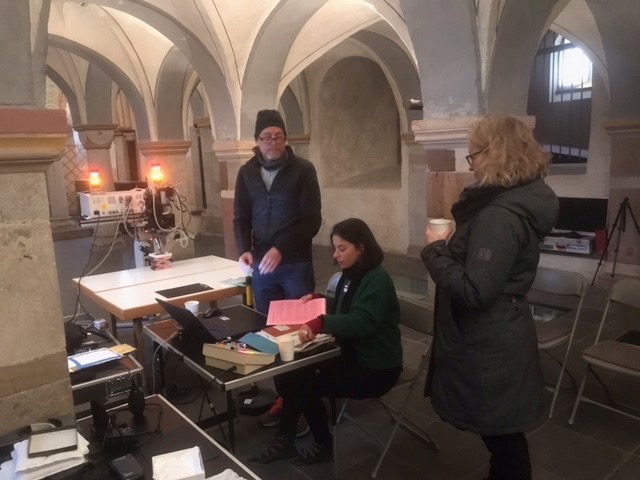

Analysis of comparative objects

Analysis of comparative objects

In order to be able to compare technological findings and analytical information on materials from the various studies on the Imperial Crown with some other goldsmith objects from the Ottonian-Salic period, three measurement campaigns were carried out in German collections in the fall and winter of 2023/24, as well as additional analyses in the Imperial Treasury in Vienna. The focus was on cloisonné enamels that have been directly associated with the Imperial Crown in the past or that offer more concrete and reliable evidence with regard to their dating and localization than the crown itself. They were examined on site using 3D microscopy, X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF), fibre optic reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) and µ-Raman spectroscopy.

The KHM's portable HIROX 3D microscope was brought to the respective locations for documentation using optical microscopy. Investigations applying the other analytical methods in Essen, Munich and Cologne were performed by our cooperation partners Stefan Röhrs and Cristina Aibéo from the Rathgen Research Laboratory of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (XRF analyses) and Thorsten Allscher from the Institute for Conservation and Restoration of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich (FORS and µ-Raman analyses).

In a total of four measurement campaigns, 17 objects set with cloisonné enamels were examined in the Essen Cathedral Treasury, the Treasury of the Residenz, the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum and the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, all in Munich, the Roman Catholic parish church of St. Severin in Cologne and the Imperial Treasury in Vienna (here without FORS and µ-Raman analyses). As varying measuring devices had to be used at the different locations, the suitable measurement parameters were defined as standards in advance together with the experts mentioned in order to ensure the comparability of the analysis data.

Altogether, this provides images and data on a total of around 350 individual cloisonné enamels, which will be included in the analysis, interpretation and comparison. Never before has there been such a comprehensive material scientific database on such enamels, which are counted among the most technically difficult and therefore most prestigious forms of decoration in medieval goldsmithing.

The remaining months until the end of the project will focus on the comprehensive evaluation of this data. It will be carried out in close cooperation with the experts already mentioned as well as other material scientists from Germany, France and Italy.

Sabine Stanek, Martina Griesser, Franz Kirchweger (23.5.2024)

Further methods

Further methods

- UV-Vis-spectroscopy on selected gemstones

- Technical photography (3,000 K, 5,000 K, UV 254 nm, UV 365 nm, IR)

- µ-computer tomography (µ-CT) of components without gemstone or pearl applications

- Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on sample material collected from organic adhesions

- Raster electron microscopic analysis (EDX-REM) on sample material collected from inorganic adhesions

Art Historical & Historical Research

Analysis of the Inscriptions on the Imperial Crown

Analysis of the Inscriptions on the Imperial Crown

The inscriptions on the enamel plates of the Imperial Crown have recently attracted increased attention from historians. In connection with certain letter shapes on the enamel plates, they argued that the crown could not have been created before the late 11th century. As a result, the CHVONRADVS named on the arch is said to have been King Conrad III (r. 1138-1152), who is subsequently also identified as the crown’s commissioner. The suggested dating is very different from that found in art historical scholarship.

Within the framework of this project, all inscriptions on the crown will be examined together with exact technological observations for the first time and the findings discussed in a direct interdisciplinary exchange.

The crown has a total of ten inscriptions. They are fashioned in four different techniques and placed across seven different components of the crown: we find both cloisonné and champlevé enamel on the four plates of the circlet, niello on the back of the central cross and, in a technically unusual form, another inscription is formed by the small threaded pearls on both sides of the arch. We aim to examine epigraphically significant aspects of these inscriptions from all angles, both in terms of their respective characteristics as graphism on the one hand and as text on the other. With regard to the graphic execution, it is not only about the style of the writing (palaeography) and its historical classification, but also about its semantic implications. The latter also concerns the arrangement of the writing and conventions of its relation to pictorial depictions. In the case of the texts, we are focusing on linguistic and orthographic circumstances as well as questions of intertextuality (relationship to other texts).

Because of this, knowledge of relevant written sources and their respective reception history is also of great importance. For instance, the texts of the banderols on the enamel panels have repeatedly been associated with the Imperial coronation liturgy in scholarly literature. Central objectives of the present analysis surrounding the inscriptions are the chronological and geographical classification of the crown and its components, combined with an effort to gain a deeper understanding of its semantic significance.

Clemens M. M. Bayer (November 23, 2022)

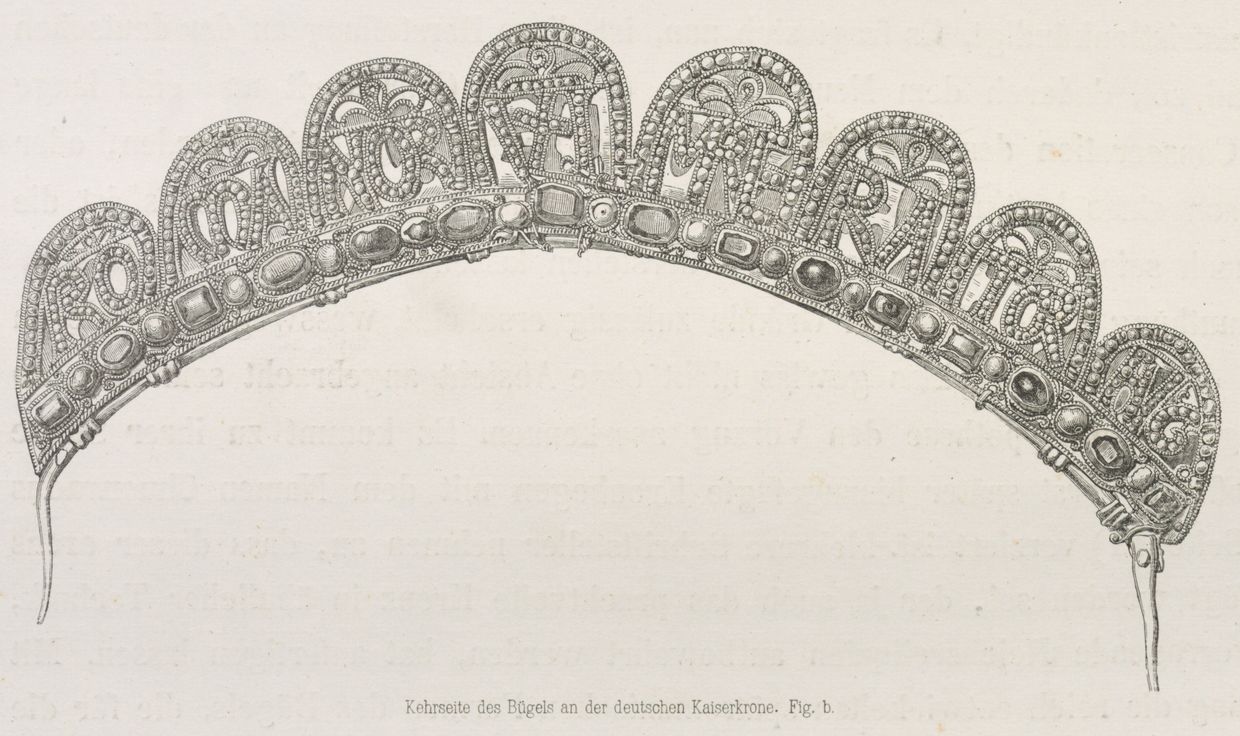

Research on pictorial sources

Research on pictorial sources

What significance might arise from historical representations of the Imperial Crown in the context of the project’s objectives? This is the central question guiding the research into the pictorial sources for this project. So far, the literature has focused primarily on identifying medieval representations of the crown. Often these pictorial sources were used to historically contextualise the shape and individual design elements of the Imperial Crown.

However, none of these images can be established with complete certainty as a representation of the Viennese crown for the period before 1500. This led to exceedingly controversial discussions of these examples in the literature. Even if a compilation of these representations hardly promises new insights for the concrete questions of the project, their systematic documentation is nevertheless planned.

Likely made as a preparatory study for his idealised portrait of Charlemagne, Albrecht Duerer’s famous drawing of the Imperial Crown (after 1510), provides a turning point in the way that the crown’s objecthood and materiality are represented. Taking into account this new approach towards more naturalistic representations in the visual arts in general, we decided to focus our research on images from the period after 1500, recording and evaluating as much material as possible. Since May 2022, around 16,000 entries in national and international image databases have been systematically searched and assessed. Based on these efforts, about 550 entries have so far been created in an internal CROWN database.

A detailed evaluation of these entries is still pending. However, one finding we can already ascertain is that while the Imperial Crown was frequently depicted after Dürer, this was rarely done in such detail that a concrete preservation state of the object could be deduced from the images. Notable exceptions like the engravings by Johann Adam Delsenbach published in 1790, the illustrations from a magnificent work by Franz Bock commissioned by Emperor Franz Joseph I and photographic prints from the early 20th century in the holdings of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, however, indeed promise new results for the questions of the project.

Evelyn Klammer (November 18, 2022)

Research on textual sources

Research on textual sources

In addition to the systematic collection of pictorial sources, we also aim to collate written historical accounts of the Imperial Crown. This will form a foundational pillar for an interwoven understanding of the object’s material history and, ideally, allow us to trace its present condition back through time. Written sources from the time the crown was deposited in Nuremberg (1424-1796) have never been systematically sifted and evaluated in relation to the crown’s present appearance and object history. An initial survey reveals that they provide valuable insight into historical repairs and interventions.

In contrast, the collection of written sources from the time before 1400, suggests hardly any new insights in this respect. This material has already been researched and debated many times. Nevertheless, we are preparing a carefully curated catalogue of these sources. Our aim is to provide a solid foundation and comprehensive account for further discussions of the crown’s fates in the Middle Ages.

These entries will adopt the following structure:

- A "header" with basic information (author, period, etc.);

- Some contextualising information of the relevant passage;

- Text excerpt (not too narrowly defined);

- Translation (as precise as possible);

- Short commentary on the development of linguistic and contextual problems (only as much as necessary);

- Most relevant cross-references of the passage in secondary literature.

Clemens M. M. Bayer, Franz Kirchweger (November 23, 2022)

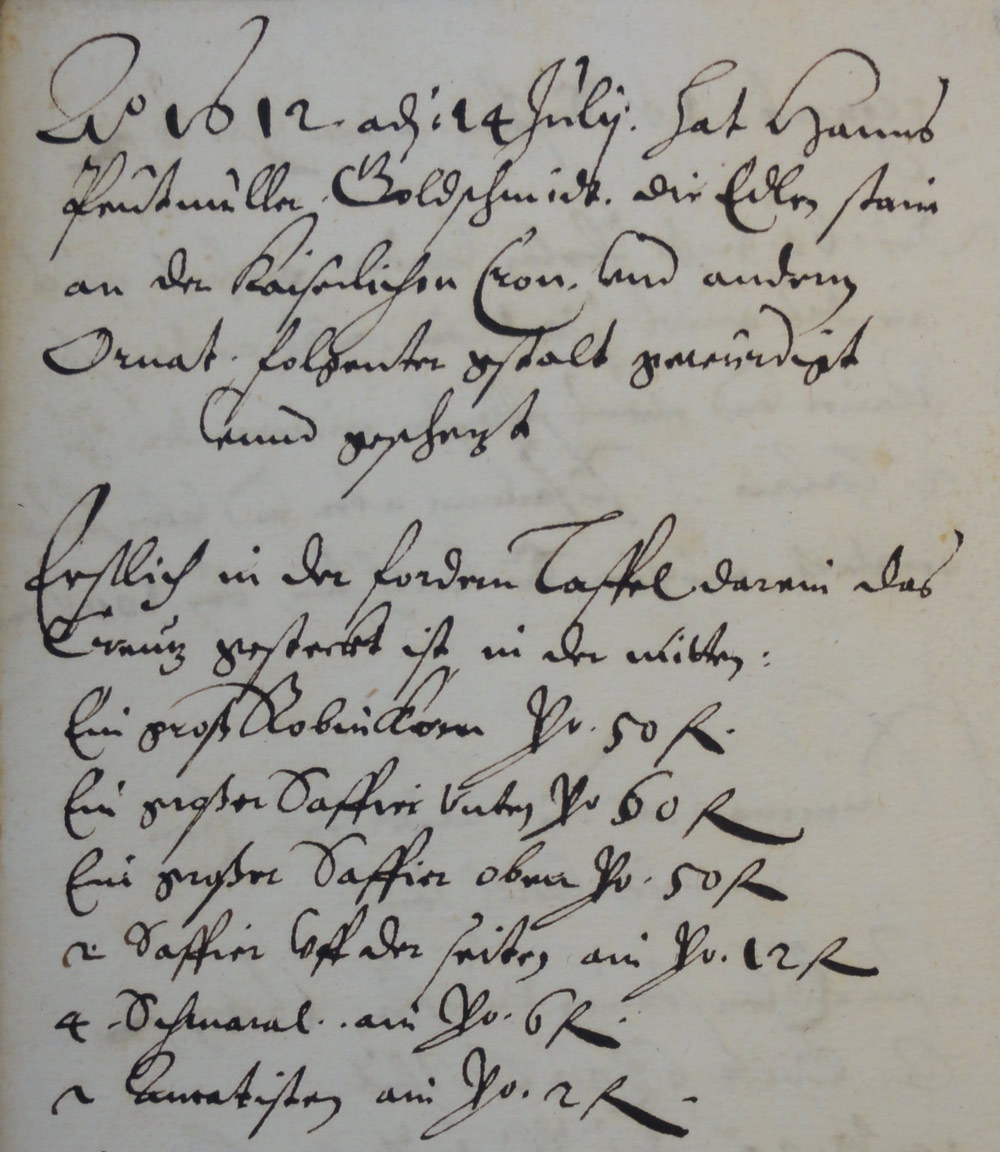

Analysis of early-modern sources in the Staatsarchiv Nuremberg

Analysis of early-modern sources in the Staatsarchiv Nuremberg

A number of references in Karl-Engelhardt Klaar’s essay on the ‘Sicherung und Pflege der Reichskleinodien in Nürnberg’ (in: Nürnberg – Kaiser und Reich, exhibition organized by the Staatsarchiv Nuremberg, Nuremberg 1986, pp. 71-82) suggested a review of early modern archival material in the Staatsarchiv Nuremberg that was likely to contain information on the use, safeguarding and maintenance/repair of the Imperial Crown and the other artefacts comprising the imperial insignia. With the help of Archivoberrat Dr Daniel Burger, we were able to examine and record the material at Nuremberg in February 2023.

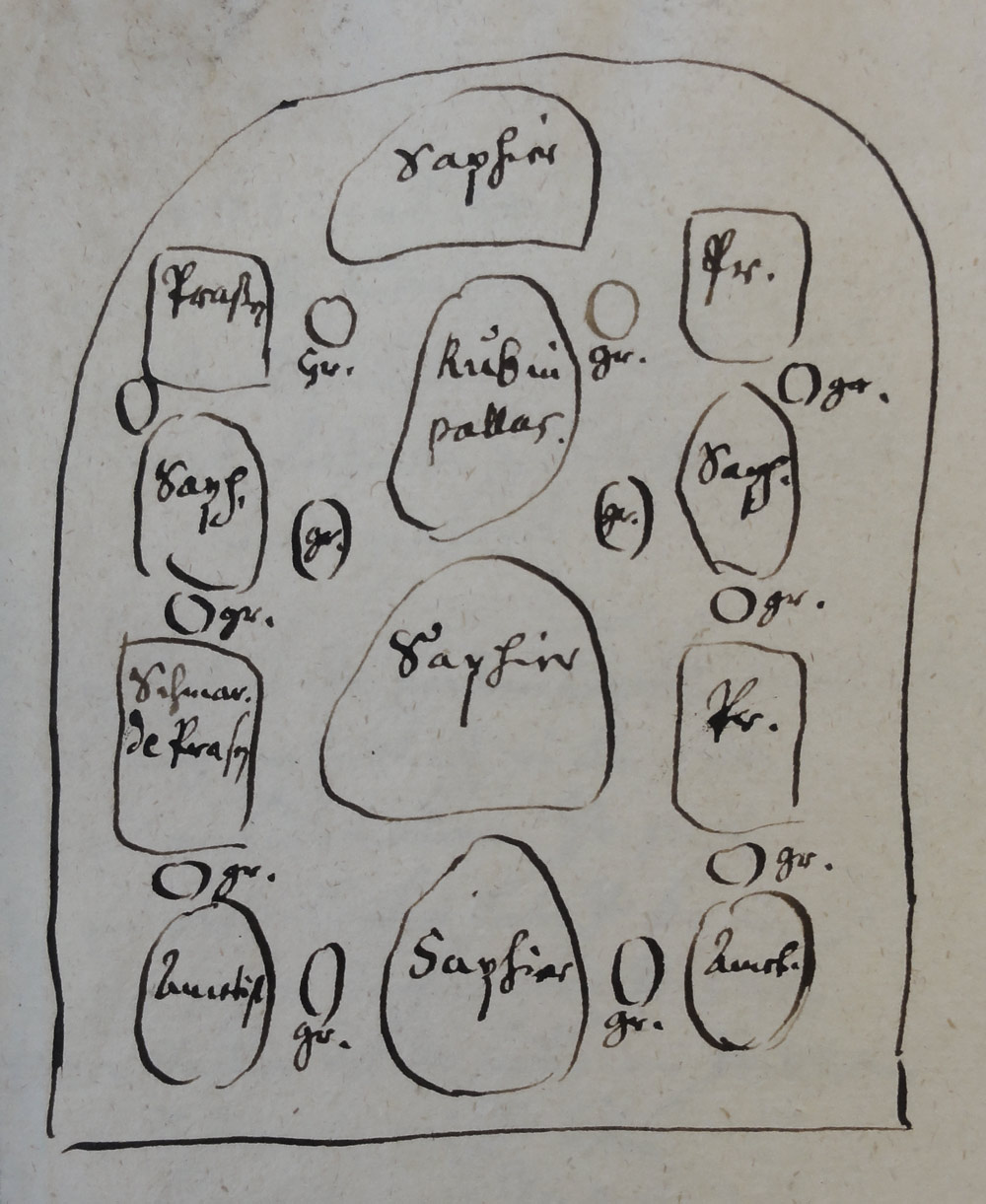

Next, Pia Metschitzer (a historian working in the KHM Archive) began to produce transcripts for our project. The sources edited so far include very interesting remarks documenting both extant and missing parts of the stone- and pearl decoration, and repairs. We have notes dating from 1521, 1612, 1619 and 1630 respectively that document audits of the crown’s components. In 1619, the audit seems to have been carried out following the coronation of Emperor Matthias I and his consort, Anne, and Hans Beutmüller (died 1622), a goldsmith first recorded in Nuremberg in 1588, was asked to evaluate the crown. Beutmüller’s appraisal includes two straightforward drawings (presumably also by him) that document the positions of the different stones decorating the various parts of the crown at that date.

Also important are receipts for payments for individual repairs carried out on the Imperial Crown in the seventeenth and eighteenth century; most, however, do not dwell in detail on the actual work and can therefore not be connected to specific interventions, but they prove that such repairs were carried out.

Franz Kirchweger (28 Sept. 2023)

Two newly discovered ancient engraved gems

Two newly discovered ancient engraved gems

In the course of our comprehensive examination of the Imperial Crown using 3-D digital microscopy [link: Technological Research / Investigation using 3D digital microscopy], we were able to photograph two previously unknown ancient intaglios included in the stone decoration. The obverses of the two engraved gems face inwards, which is why they are not visible from the outside under normal conditions.

The amethyst positioned in the lower row of the front plate (A) on the left shows a harbour scene with ships; the engraved gem set in the lower row of the back plate (E) depicts a half-length maenad holding a theatre mask. The examination was carried out by Prof Erika Zwierlein-Diehl of the University of Bonn, a leading international expert on ancient glyptic art and its afterlife who has published numerous works on the ancient gems and cameos in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

According to her preliminary research, the intaglio featuring a maenad is the earliest and most beautiful version of a type of which only a few examples have come down to us. It is the work of a Greek master active in the middle or third quarter of the first century B.C, i.e. during the transition from the late Hellenistic style to Augustan classicism. The gem showing a harbour scene was executed in the so-called miniature style and produced sometime between the end of the first century B.C. and the first century A.D. It is the most detailed example of the twelve extant cameos featuring harbour scenes.

Franz Kirchweger (28 Sept. 2023)

Technological Research

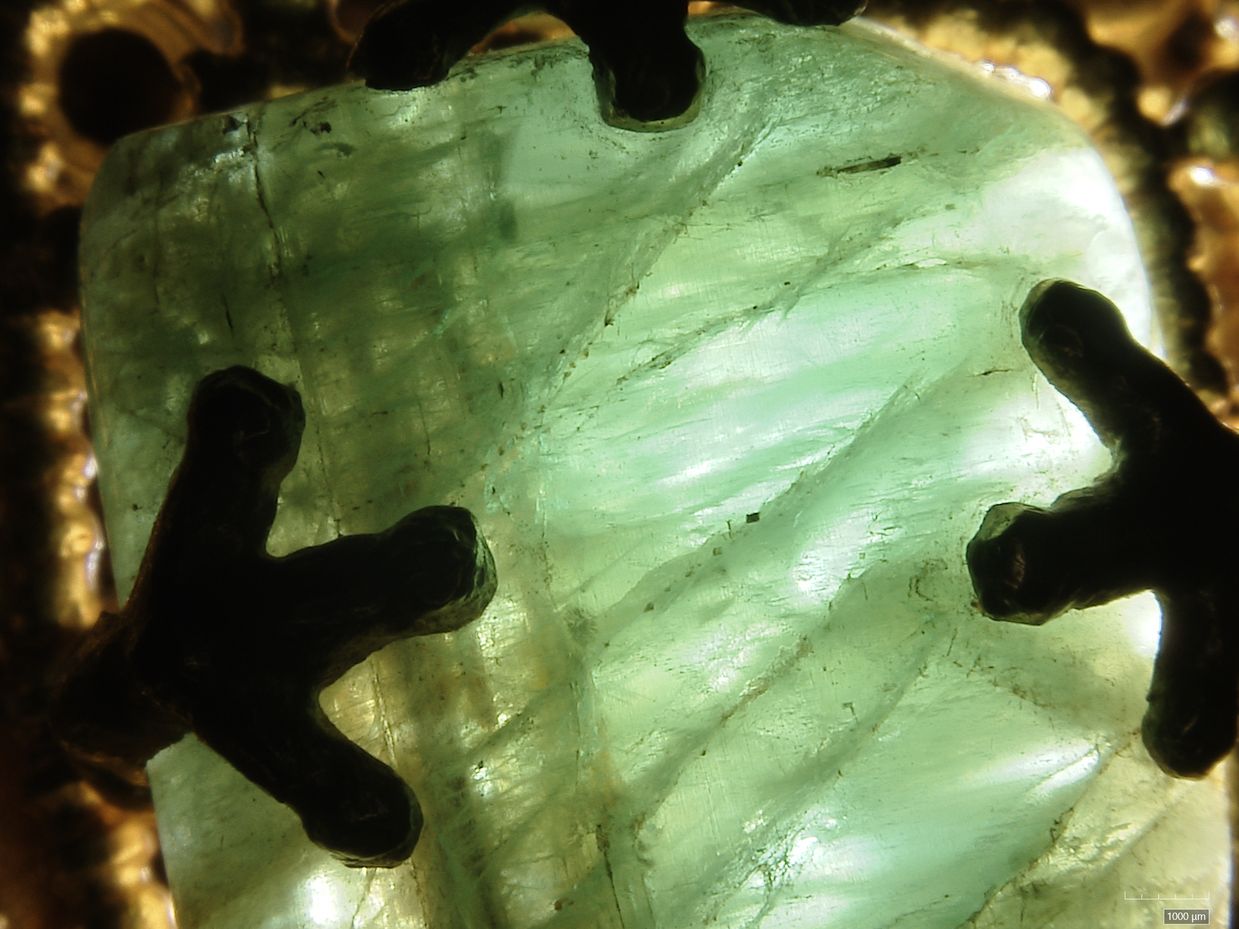

3D Digital Microscopy

3D Digital Microscopy

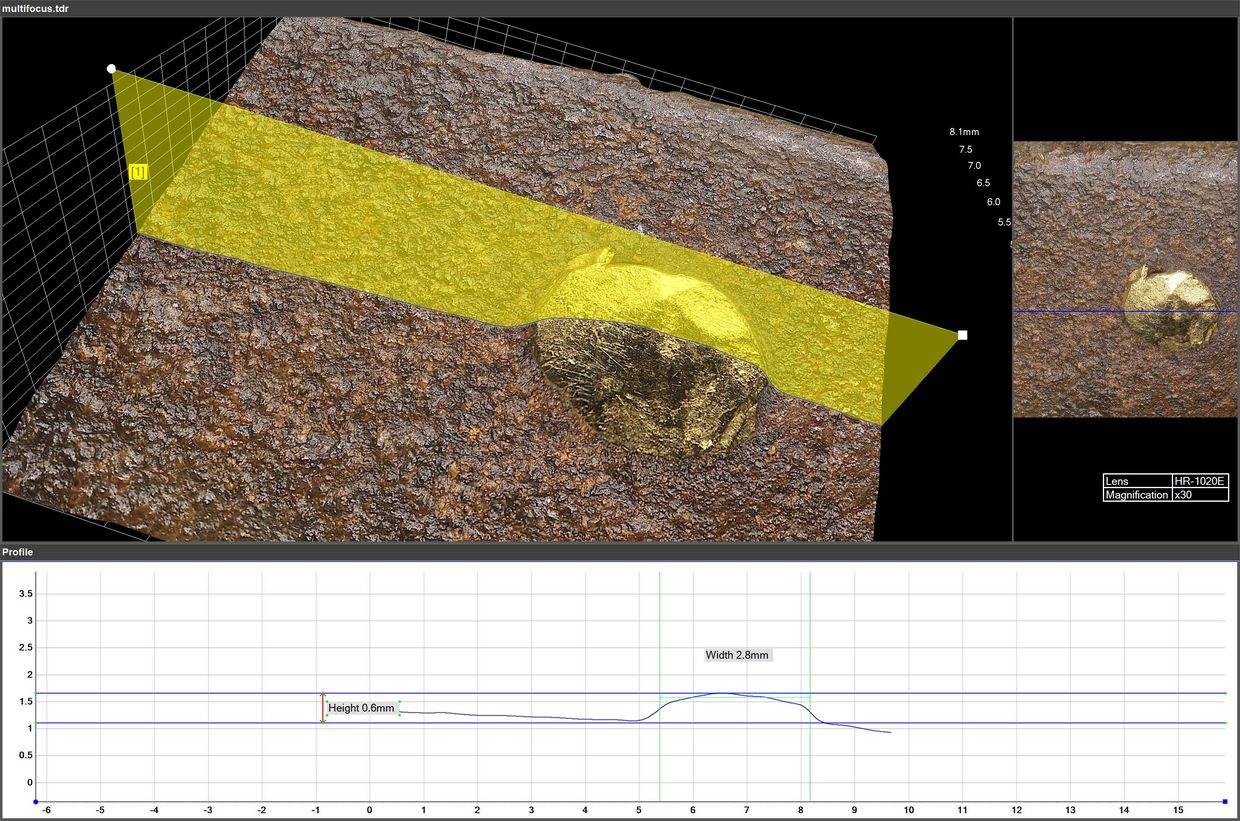

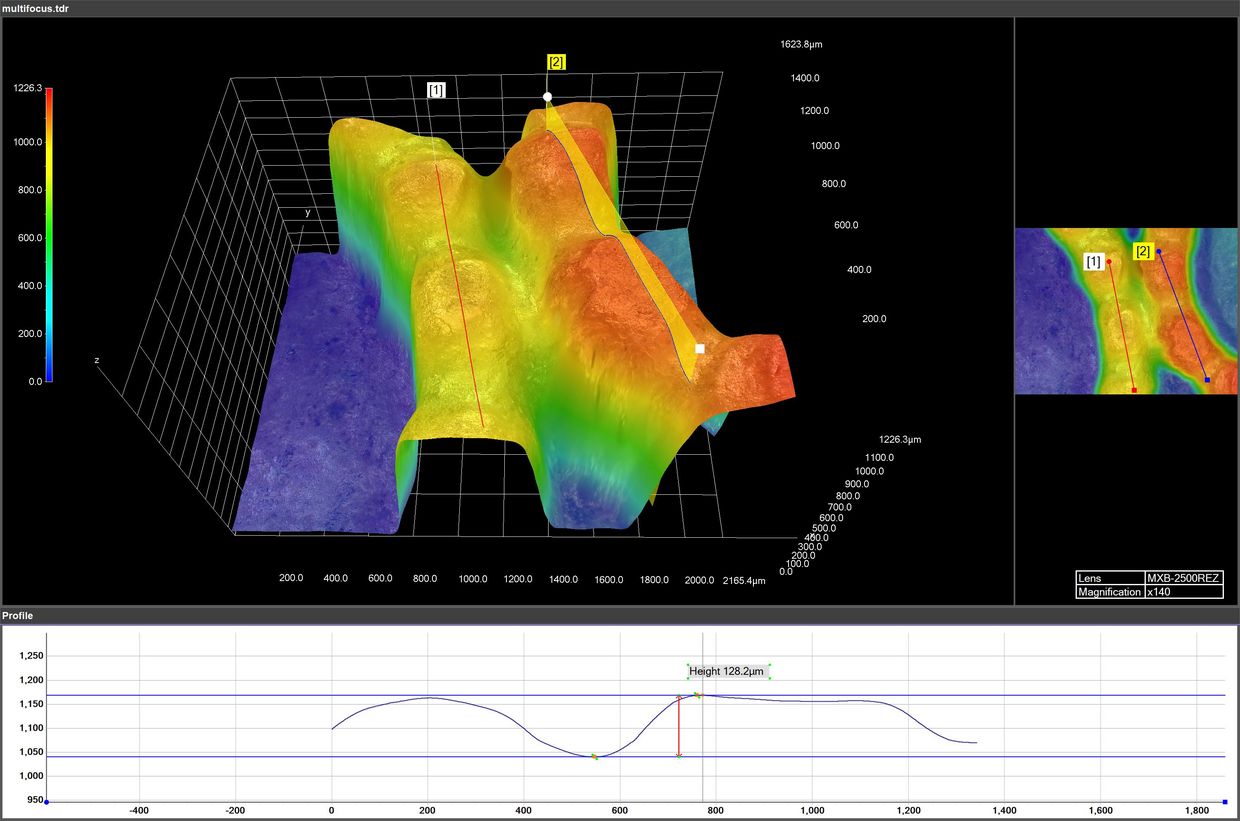

The systematic optical assessment and photographic documentation of the Imperial Crown is a central objective of this research project. This will enable us to understand the crown’s technological construction, materiality and state of preservation at an unprecedented level of quality and detail. We use a 3D digital microscope (HIROX HRX-01) to comprehensively examine the crown as well as some other relevant objects of close comparison. This allows us to record the object’s surface morphology and measurements of individual construction parts and decorative elements in a wide range of magnification (10x -2500x). Moreover, we can create 3D- and panoramic views of important areas in high resolution and with high depth of field.

During our first investigation campaign (March to July 2022), we focused on the technological examination of the goldsmith's work and gemstone settings. In preparation for Raman measurements, 172 gemstones were examined microscopically and photographed in reflected as well as polarised light. In a next step, we recorded characteristic inclusions in the crown’s gemstones and then photographed these in different light settings with the 3D microscope. During this campaign, we also individually examined a total of 824 formal and functional components of the goldsmith's work (gemstone and pearl settings, decorative elements, as well as hinges, sleeves and tubes) and photographed them from different angles.

We typified indicators of interventions (repair wires and soldering, addition of stabilising materials, modifications, hole drilling, rivets) to link them to historical damage and even identifiable reworking events.

As the crown ring is fixed in its octagon position, taking distortion-free images of the individual plates’ backside presented a particular challenge.

For this purpose, we constructed a custom table with an octagonal opening. We also extended the 3D microscope by a FlexArm, so that the lens could be manoeuvred into the crown’s inside from below. Following this initial campaign, for the first time, we now have distortion-free scans of the Imperial Crown in its entirety. This includes high-resolution images (30x magnification) of all plates of the coronet (front, back, upper edge, lower edge), of the arch (both sides, upper edge, lower edge), of the central cross (front, back) as well as the enamel plates (here also at 90x magnification in incident light and grazing light).

Helene Hanzer, Teresa Lamers,

Herbert Reitschuler, Sabine Stanek (November 28, 2022)

Technical drawings

Technical drawings

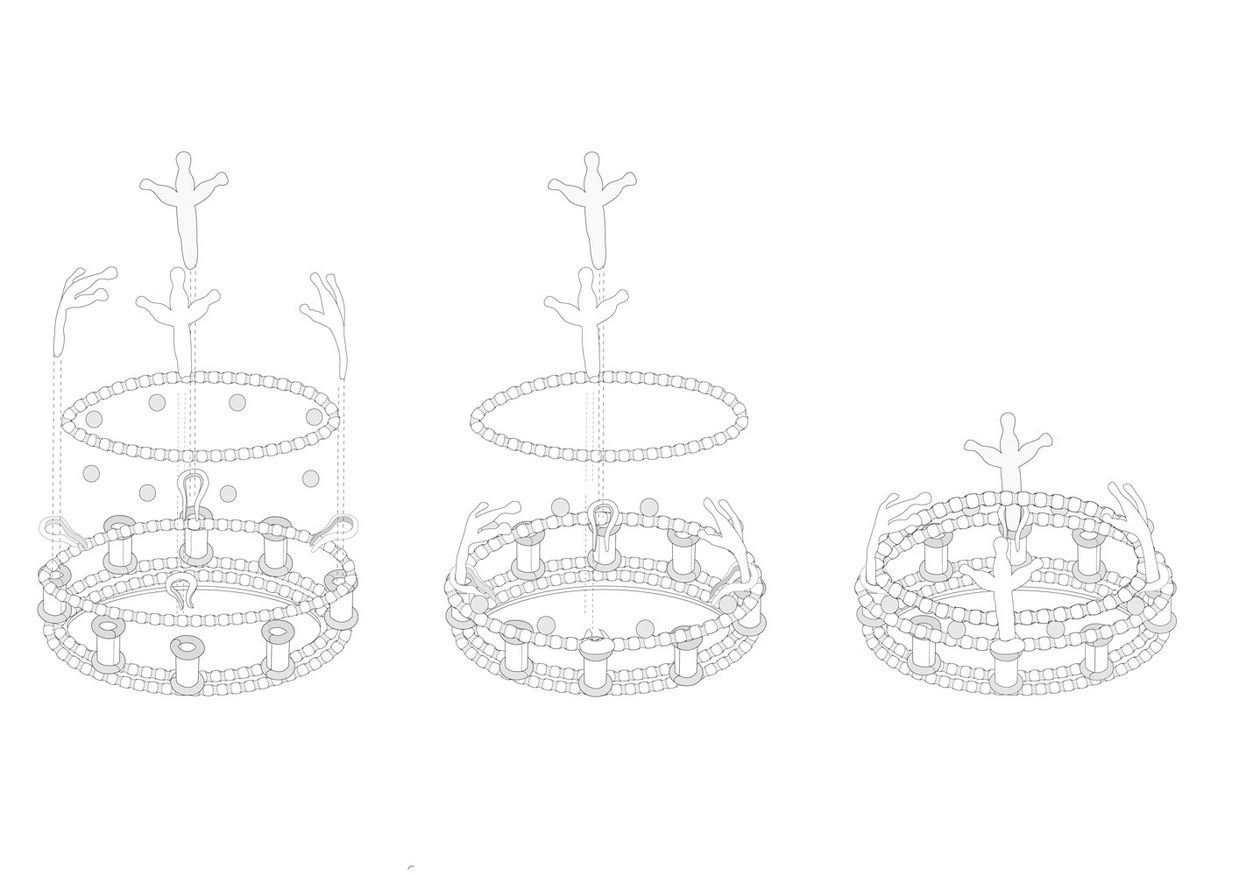

The main focus of the investigations into the manufacturing technique is on the techniques used, the constructive details and the formal characteristics of the individual components of the crown. The observations and findings gained from the optical examinations and photographic documentation are continuously elaborated in writing and recorded in the CROWN database. In addition, Herbert Reitschuler produces technical drawings of various kinds. These include exploded views of the construction of the individual types of stone and pearl settings, which make it possible to illustrate the complex construction and function of the components. As an example, a drawing of the type "high mount for stones with three-fingered claws" is shown here and contrasted with a photograph. All settings of this type for the large stones on the crown‘s circlet follow the same construction principle, which was individually adapted to the respective size and shape of the stone.

Helene Hanzer (4. 10. 2023)

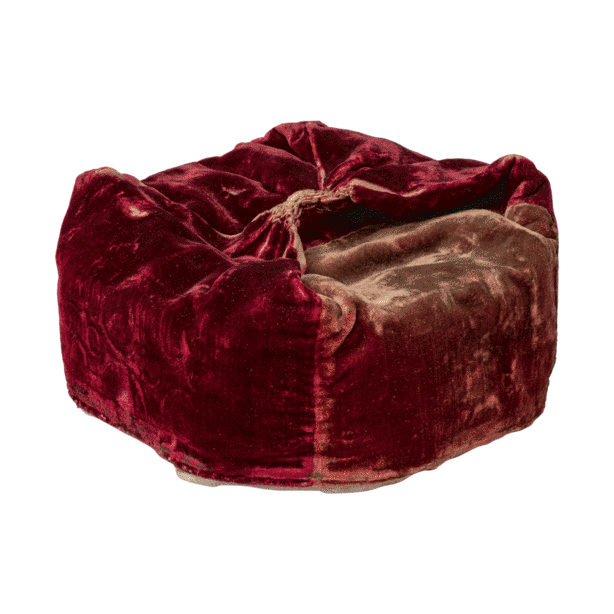

Examination of the Velvet Cap

Examination of the Velvet Cap

In the course of CROWN, for the first time the Velvet Cap will also be subjected to a technological and art-historical examination.

The preserved cap was created much later than the crown itself, but played a major role in the course of the coronation ceremonies. During fittings and adjustments of the regalia before the actual coronations, which are mentioned in numerous reports of the 17th and 18th centuries by Nuremberg envoys, it was not only adjusted with the help of padding on the inside, some of which is flexible and can be removed. Apparently, they were also sewn to the crown if necessary, which can be deduced from surviving thread remnants and traces of sewing.

The structure of the multi-layered cap, which was sewn together from two different pieces of silk velvets, will continue to be the focus of investigation in the course of the project in order to gain additional insights into the genesis of the cap and the adaptations in the course of the coronations.

In addition, technological analyses of the dyes, the specific weave types of the fabrics and the cut are currently being prepared. Together with the information found in the historical text sources and art historical observations, these analyses are expected to provide many more insights into the history of the cap’s creation and its use in connection with the Imperial Crown.

Katja Schmitz-von Ledebur, Sabine Svec (7. Juni 2024)

Who were our partners?

The KHM project team brought together art historians, conservators, and scientists, benefiting from their expertise, know-how, and respective approaches to develop a collaborative and interdisciplinary research platform.

Moreover, we discussed and debated preparation, implementation, and findings with international experts from relevant specialized fields, to share experiences and discuss methods and aims.

Numerous specialists and colleagues kindly agreed to support the project by discussing and sharing ideas. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to them for their support, as well as equally thanking the colleagues from within KHM Museumsverband who gave their advice and practical support to the project team in the collection and analysis of data (Maja Gušavac, Peter Kloser, Werner Mahlknecht, Henje Richter, Hanna Schneck), the technological examinations (Nikoletta Sárfi, Andreas Uldrich), and the registration of historical records (Susanne Hehenberger).

Conservation Sciences

- Helene Hanzer

- Teresa Lamers

- Herbert Reitschuler

Sciences

- Martina Griesser

- Sabine Stanek

- Katharina Uhlir

Art History

- Franz Kirchweger

- Evelyn Klammer

- Pia Metschitzer

Organizational support: Dominik Cobanoglu, Doris Prlic, Julia Spitaler, Stella Wisgrill

External Experts

- Maurizio ACETO,

Dept . Scienze e Innovazione Tecnologica , Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale "Amedeo Avogadro", Alessandria - Angelo AGOSTINO,

Dipartimento di Chimica – Sezione Materiali Inorganici, Università di Torino - Cristina AIBÉO,

Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz - Thorsten ALLSCHER,

Institut für Bestandserhaltung und Restaurierung, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München - Clemens M. M. BAYER,

Bonn/Lüttich - Klaus Gereon BEUCKERS,

Kunsthistorisches Institut der Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel - Harals DRÖS,

Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Heidelberg - Birgitta FALK,

Domschatzkammer, Aachen - Andrea FISCHER,

Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Stuttgart - Monica GALEOTTI,

Opificio delle Pietre Dure e Laboratori di Restauro

- H. Albert GILG,

Lehrstuhl für Ingenieurgeologie, Technische Universität München - Matthias HEINZEL,

Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie (LEIZA) (bis 31.12.2022: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum RGZM) - Klaudia HRADIL,

Röntgenzentrum der Technischen Universität Wien - Stefanos KARAMPELAS,

Laboratoire Français de Gemmologie, Paris - Ludger KÖRNTGEN,

Historisches Seminar, Arbeitsbereich Mittelalterliche Geschichte, Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz - Lothar LAMBACHER,

Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz - Werner MALECZEK,

Institut für österreichische Geschichtsforschung, Universität Wien - Lutz NASDALA,

Institut für Mineralogie und Kristallographie der Universität Wien - Michael PETER,

Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg

- Martina PIPPAL,

Kunsthistorisches Institut, Universität Wien - Ina REICHE,

Institut de recherche de Chimie Paris (IRCP) und Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF), Paris - Stefan RÖHRS,

Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz - Romedio SCHMITZ-ESSER,

Historisches Seminar, Universität Heidelberg - Bernd SCHNEIDMÜLLER,

Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Heidelberg - Sebastian SCHOLZ,

Historisches Seminar, Universität Zürich - Hiltrud WESTERMANN-ANGERHAUSEN,

Köln - Viola WINKLER, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

- Andreas ZAJIC,

Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien - Erika ZWIERLEIN-DIEHL,

Klassische Archäologie, Universität Bonn

What else were we working on?

This section offers information about activities regarding content and organization that the CROWN team worked on in addition to the various ongoing examinative undertakings.

These included lectures and publications, and the analysis of the extensive data generated by our examinations in order to make this information available online once the project has concluded; we also shot a film that documents the work of the CROWN team at various phases of the project.

On 30 January 2023, the Kunsthistorisches Museum held a press conference on the project that was widely covered in the media. For press releases click here.

International Conference

Vienna, 26–27 June, 2025

Weltmuseum Wien, Forum, Neue Hofburg, 1010 Vienna

From June 26 to 27, international experts were invited by the Kunsthistorisches Museum to present observations and findings on material-analytical, art-technological, historical, and art-historical questions that were central to the three-year CROWN Research Project: Investigations into the Materiality, Technology, and Condition of the Imperial Crown of Vienna.

The interdisciplinary approach of the CROWN project also provided the conceptual framework for the presentations. Experts from the fields of art and historical sciences, earth sciences, natural sciences, and conservation science offered insights into their research on various aspects of the Imperial Crown and other goldsmith works from the Ottonian-Salian peiod. Research traditions were critically reflected upon, the possibilities and limitations of different disciplinary approaches were discussed, and investigations and considerations regarding the various components of the crown itself were brought into focus.

The diversity of perspectives and the exchange between disciplines clearly demonstrated how complex the Imperial Crown is in terms of its composition and history. It also became evident that the findings of the different disciplines—especially regarding dating—must, for the time being, continue to coexist without resolution. At the same time, however, it became apparent that current research shows a fundamentally greater awareness of the many gaps in textbook knowledge and in the corpus of objects, meaning that today’s state of knowledge only permits very limited definitive statements and conclusions. In this context, acknowledging open questions was seen as more meaningful than constructing new hypotheses that could immediately be called into question.

The contributions the project made to numerous areas of fundamental research received wide recognition. It is of great relevance for further research on the crown itself, on cloisonné enamel of the early and high Middle Ages, and on the origin and use of gemstones and pearls in medieval goldsmithing in the Latin West. The final publication of the CROWN project, currently in preparation and scheduled for release in 2026, will provide a broad and comprehensive foundation for future research.

Isabella Schwarzer / Franz Kirchweger (10. Juli 2025)

Lectures & Workshops

Lectures & Workshops

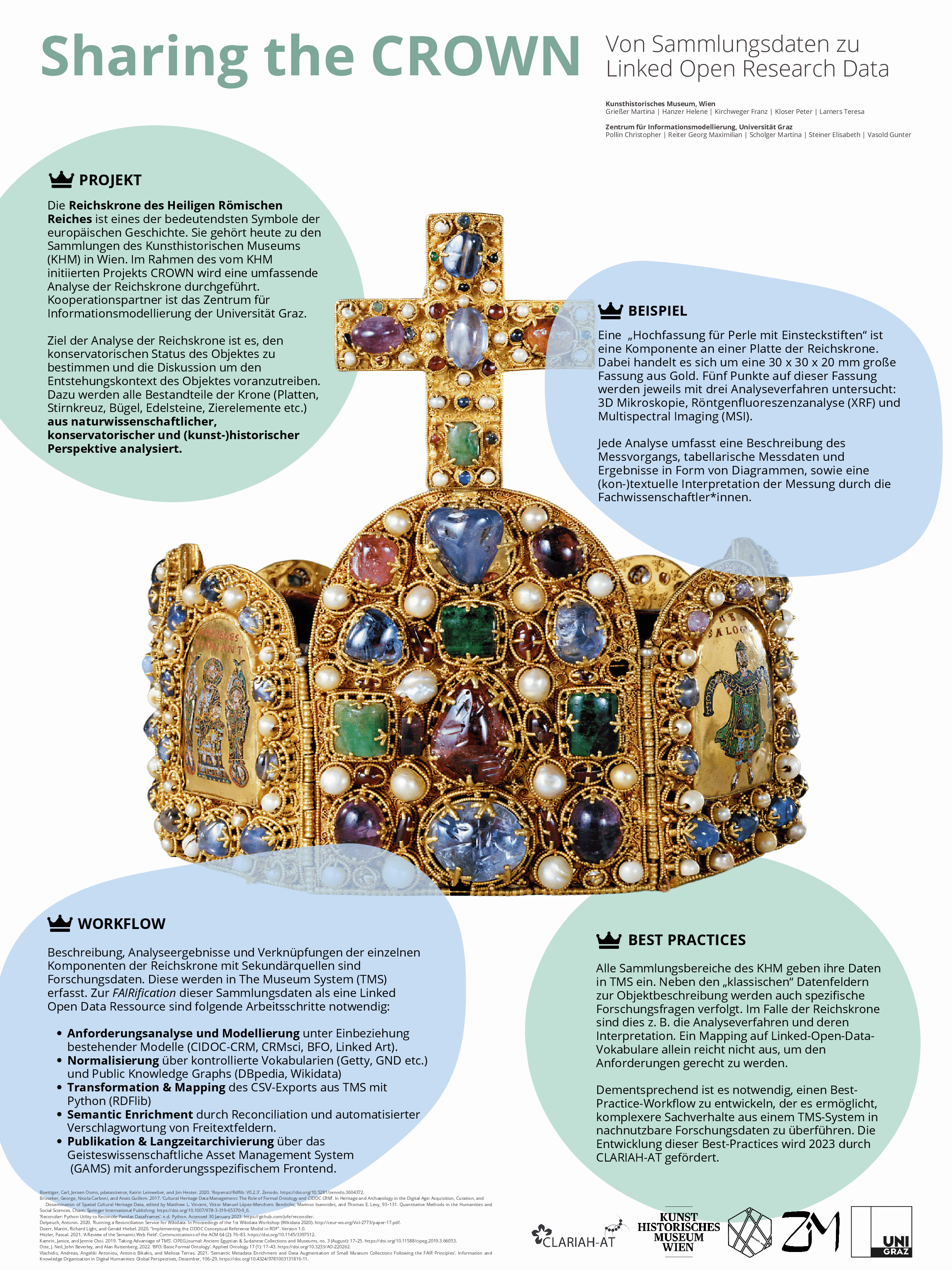

- Christopher Pollin, Martina Scholger, Elisabeth Steiner et al., Poster presentation ’Sharing the CROWN – Von Sammlungsdaten zu Linked Open Research Data’, poster presentation on the occasion of the Annual Conference of the Association ’Digital Humanities in the German-speaking World’ Trier and Luxembourg, 13–27 March 2023

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘CROWN. Ein interdisziplinäres Forschungsprojekt zu Materialität, Technologie und Erhaltungszustand der Wiener Reichskrone‘, lecture on the occasion of the conference ‚Nicolaus Virdunensis Fabricavit. Das Goldschmiedewerk des Nikolaus von Verdun im Stift Klosterneuburg – Materialtechnologie und kunsthistorische Perspektiven’, Klosterneuburg, 11–13 May 2023

- Teresa Lamers, ‘Where conservators meet mineralogists: The CROWN project - an interdisciplinary study of the Imperial Crown’, lecture at the Institute of Mineralogy and Crystallography of the University of Vienna, 23 June 2023

- Martina Griesser, ‘The splendour of the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire – Illuminating the gemstones by photoluminescence and Raman spectroscopy’, lecture on the occasion of the 19th Confocal Raman Imaging Symposium, Ulm, 25–27 Sept. 2023

- Hanna Schneck, ‘Das Crown-Projekt am Kunsthistorischen Museum Wien", lecture on the occasion of the Goobi Days, Göttingen, 26–27 Sept. 2023

- Roundtable ‘Die Wiener Reichskrone – Historische und Kunsthistorische Fragestellungen’, Vienna, 16–17 June 2023.

Participants

Clemens M.M. Bayer (Liège/Bonn), Klaus Gereon Beuckers (Kiel University), Harald Drös (Academy of Sciences, Heidelberg), Birgitta Falk (Aachen Cathedral Treasury), Martina Griesser (KHM, Vienna), Helene Hanzer (KHM, Vienna), Franz Kirchweger (KHM, Vienna), Ludger Körntgen (Mainz University), Teresa Lamers (KHM, Vienna), Werner Maleczek (University of Vienna), Michael Peter (Abegg Foundation, Riggisberg), Martina Pippal (University of Vienna), Herbert Reitschuler (KHM, Vienna), Romedio Schmitz-Esser (University of Heidelberg), Sebastian Scholz (University of Zurich), Hiltrud Westermann-Angerhausen (Cologne), Andreas Zajic (Academy of Sciences, Vienna).

Organisational and technical support

Dominik Cobanoglu, Stefan Braith and Jana Schuller-Frank.

CROWN invited the above-mentioned experts on the history and the history of art of the early and high Middle Ages to discuss the objectives and status quo of the project and to exchange views in direct conversation on the different dating approaches and the associated arguments. As expected, there were no simple and quick solutions to the question of dating, but there was great interest and a willingness to discuss this and other important questions (original function, relationship of the individual components to each other, chronology of important comparative objects) further.

Participants in the roundtable discussion on 16–17 June 2023 in Vienna

- Workshop ‘Interdisziplinäres Forschungsprojekt CROWN’, Vienna, 21–22 September 2023.

Participants: Maurizio Aceto (Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale, Alessandria), Cristina Aibeo (Rathgen Research Laboratory, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - SPK), Thorsten Allscher (Institute for Conservation and Restoration, Bavarian State Library, Munich), Clemens M.M. Bayer (Liège/Bonn), Andrea Fischer (State Academy of Fine Arts, Stuttgart), Martina Griesser (KHM, Vienna), Helene Hanzer (KHM, Vienna), Matthias Heinzel (Leibniz Centre for Archaeology - LEIZA, Mainz), Franz Kirchweger (KHM, Vienna), Ludger Körntgen (University of Mainz), Lothar Lambacher (Museum of Decorative Arts, National Museums in Berlin - SPK), Teresa Lamers (KHM, Vienna), Ina Reiche (Institut de recherche de Chimie Paris (IRCP) and Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France, Paris); Herbert Reitschuler (KHM, Vienna), Stefan Röhrs (Rathgen Research Laboratory, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - SPK), Sabine Stanek (KHM, Vienna); Katharina Uhlir (KHM, Vienna).

Organisational and technical support

Dominik Cobanoglu, Julia Spitaler.

On 21-23 Sept. 2023 we organized a meeting in Vienna - a follow-up event to a video conference held on 4 Nov. 2022 - that brought together conservation scientists, historians and art historians to discuss initial results and findings, open questions and additional perspectives, and to share assessments and expertise. A main focus was on the analysis of the enamel plates.

Participants in the CROWN workshop on 21–22 September 2023 in Vienna

- Teresa Lamers, ‘Anwendung verschiedener Analysemethoden zur Identifizierung der für die Reichskrone verwendeten Materialien’, lecture on the occasion of the exhibition ‘Conservator at Work‘, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, 9 Nov. 2023

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘CROWN. Untersuchungen zu Technik, Materialität und Erhaltungszustand der Wiener Reichskrone. Eine Zwischenbilanz’, lecture at the Institut für Geschichte at Vienna University (in cooperation with the Institut für die Erforschung der Frühen Neuzeit), Vienna, 13 Dec. 2023

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘The Imperial Crown in Vienna and its Enamels’, lecture on the occassion oft he 59th International Congress of Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo (MI), 10 May 2024

- Franz Kirchweger, Teresa Lamers, ‘CROWN. Ein interdisziplinäres Forschungsprojekt zur Wiener Reichskrone’, lecture & colloquium at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, 7 June 2024

- Franz Kirchweger, ’CROWN. Aktuelle Forschungen zu Technik, Materialität und Erhaltungszustand der Wiener Reichskrone’, lecture on the occasion of the series Junge Mittelalterforschung, Museum unterm Trifels, 21 Aug. 2024

- Christopher Pollin and Martina Griesser, ‘Sharing the CROWN – Establishing a Workflow from Collecting Data to Linked Research Data’, poster presentation at CLARIAH-AT-Roadshow, Paris Lodron University Salzburg, 13 Sept. 2024

- Teresa Lamers, ‘Erkenntnisse zu den vier Emailtafeln der Reichskrone auf der Basis optischer und materialanalytischer Methoden’, lecture on the occasion of the VII. Forum Kunst des Mittelalters, University of Jena, 25–27 Sept. 2024

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘Leuchtende Steine. Facetten von Transparenz und Diaphanie in der ottonisch-salischen Goldschmiedekunst’, lecture on the occasion of the VII. Forum Kunst des Mittelalters, University of Jena, 25–27 Sept. 2024

- CROWN workshop ‘Kunst- und geschichtswissenschaftliche Fragestellungen’, Heidelberg, 24–25 Sept. 2024 (organized in collaboration with Heidelberg Academy of Humanities and Sciences and University of Heidelberg)

Participants

Clemens M. M. Bayer (Liège/Bonn), Kathrin Berghoff (University of Heidelberg), Klaus Gereon Beuckers (University of Kiel), Harald Drös (Heidelberg Academy of Humanities and Sciences), Birgitta Falk (Aachen Cathedral Treasury), Martina Griesser (KHM, Vienna), Helene Hanzer (KHM, Vienna), Martin Hoernes (Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung), Dorothee Kemper (German Society for Studies in Art History, Berlin), Franz Kirchweger (KHM, Vienna), Ludger Körntgen (University of Mainz), Lothar Lambacher (form. Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin), Teresa Lamers (KHM, Vienna), Tino Licht (University of Heidelberg), Werner Maleczek (University of Vienna), Rebecca Müller (University of Heidelberg), Michael Peter (Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg), Martina Pippal (Universität Wien), Herbert Reitschuler (KHM, Wien); Romedio Schmitz-Esser (University of Heidelberg), Bernd Schneidmüller (University of Heidelberg), Sebastian Scholz (University of Zurich), Sabine Stanek (KHM, Vienna), Katharina Uhlir (KHM, Vienna), Hiltrud Westermann-Angerhausen (form. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne), Andreas Zajic (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna)

Organizational support

Daria Soboleva.

Participants, round table discussion, 24–25 September 2024 in Heidelberg

- Martina Griesser, ‘Studying the materials and technology of the Imperial Crown in Vienna: Insights into a still ongoing interdisciplinary, multi-analytical research project’, lecture on the occasion of IConS 2024 – International Conservation and Science Conference, Hungarian National Conservation Centre – Museum of Fine Arts (OMRRK), Budapest, 3–4 Oct. 2024.

- CROWN workshop ‘Enamels on the Imperial Crown and comparable objects’, 7–8 Oct. 2024, Vienna

Participants

Maurizio Aceto (Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale, Alessandria), Cristina Aibéo (Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – SPK), Thorsten Allscher (Institute of Conservation (IBR), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich), Marie Godet (Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France, Paris), Martina Griesser (KHM, Vienna), Franz Kirchweger (KHM, Vienna), Teresa Lamers (KHM, Vienna), Herbert Reitschuler (KHM, Vienna), Ina Reiche (Institut de recherche de Chimie Paris [IRCP] and Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France, Paris), Stefan Röhrs (Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – SPK), Nikoletta Sárfi (KHM, Vienna), Sabine Stanek (KHM, Vienna), Katharina Uhlir (KHM, Vienna)

Organizational support

Julia Spitaler

Participants, round-table discussion, 7–8 October 2024 in Vienna

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘Kaiser Konrad II. und die Insignien des Reiches’, lecture on the occasion of the series Inszenierung der Macht im Mittelalter, Alter Dom St. Johannis, Mainz, 16 Oct. 2024

- Franz Kirchweger, ‘Unter der Lupe. Aktuelle Forschungen zur Wiener Reichskrone’, lecture on the occasion of the research colloquium Geschichtswissenschaft in der Diskussion, University of Innsbruck, 4 Nov. 2024

- Clemens M. M. Bayer, ‘La courrone du Saint-Empire (Vienne, Trésor imperial): status quaestionis. Enjeux et ambitions d’un projet de recherche international et interdisciplinaire’, lecture on the occasion of the 14th study day FRS-FNRS, Liège, 8 Nov. 2024

- Teresa Lames, ’Conservation studies on the imperial crown – embedded in an interdisciplinary research project’, lecture (remote) on the occassion of the Ulrich Schiessl PhD colloquium at Universitat Politècnica de València, 19–20 Nov. 2024

- Christopher Pollin, Christian Steiner, and Hanna Schneck, ‘So komplex ist die CROWN. Best Practices für die Erstellung und Modellierung von Linked Open Data’, lecture on the occasion of the 10th Digitale Bibliothek, ‘Zurück (und) in die Zukunft’, Department of Digital Humanities, University of Graz, 28–29 Nov. 2024

- Franz Kirchweger (together with Martina Pippal), ‘Die Forschung zur Wiener Reichskrone. Rückblicke, Einblicke, Ausblicke’, lecture for the Association of the Friends of the Austrian Academy of the Sciences, Vienna, 4 Dec 2024

Digital project data

Digital project data

CROWN is generally committed to the international FAIR principles (‘findable, accessible, interoperable, re-usable’) with regards to the administration and processing of the generated digital data on the Imperial Crown’s circa 1,750 components. Starting point for the gathering of data in different formats (text, image, and measuring data) is the KHM Museumsverband’s long-established object databank ‘The Museum System’ (TMS). However, the FAIRification of this data as a Linked Open Data Resource required a number of separate steps (modelling, normalization, transformation and mapping, semantic enrichment) that were connected with an independent research project ‘Sharing the Crown. Von Sammlungsdaten zu Linked Open Research Data’. A first phase of data preparation was kindly supported by CLARIAH-AT:

https://digital-humanities.at/en/dha/s-project/sharing-crown-establishing-workflow-collection-data-linked-research-data

This was implemented in collaboration with the Zentrum für Informationsmodellierung at the University of Graz (Christopher Pollin, Georg Maximilian Reiter, Martina Scholger, Elisabeth Steiner, Gunter Vasold, Christina Burgstaller), providing an important basis for the publication and long-term archiving of a significantly larger number of research data than would have been possible within the confines of a book publication. Publication in the certified research data repository ‘Geisteswissenschaftliches Asset Management System – GAMS’ had originally been planned, but could not be realized during the project period for a lack of funding.

In 2023, the open source software Goobi (intranda GmbH) was installed at KHM Museumsverband. Developed for the coordination of digitization projects on library holdings and image data, it was subsequently adapted in several stages to specifically suit this project. The next stage will follow in 2025, using the tools of the Goobi viewer to make large amounts of image-based research data openly accessible and recoverable via various filter and search functions.

Documentary film

Documentary film

Commissioned by the TV stations ORF and ARTE, and in collaboration with the Kunsthistorisches Museum, EPO-Film produced a documentary directed by Klaus T. Steindl that accompanied the CROWN team during the different phases of the project in 2023/2024. Though the focus is on the ideas, objectives, procedures, and insights connected with the examinations, the film also recounts the history of the Imperial Crown over the centuries and its importance in the context of European history. The production was supported by the Fernsehfond Austria and the Filmfond Wien. The film is distributed by ORF Enterprise. It premiered on ORF 2 on 19 December 2024.

Publications

Publications

- Lutz Nasdala – Teresa Lamers – H. Albert Gilg – Chutimun Chanmuang N. – Martina Griesser – Franz Kirchweger – Annalena Erlacher – Miriam Böhmler – Gerald Giester, ‘The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, Part I: Photoluminescence and Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Gemstones’, in: The Journal of Gemmology 38/5, 2023, 448–473

- Lutz Nasdala – Teresa Lamers – H. Albert Gilg – Chutmin Chanmuang N. – Martina Griesser – Franz Kirchweger – Annalena Erlacher – Miriam Böhmler – Gerald Giester, ‘Gem Spinel in the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire: Evidence for Very Early Gemstone Heating?’, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft 169, 2023, 206 f.

- Erika Zwierlein-Diehl, ‘Drei antike Amethyst-Intaglien an der Wiener Reichskrone’, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts in Wien 92 (2023), 333–351

- H. Albert Gilg, Teresa Lames and Stefanos Karampelas, ’The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire Part II: Geographic origin of gems and Historical Context’, The Journal of Gemmology 40/1 (2025) (forthcoming)

- Teresa Lamers, Franz Kirchweger, Helene Hanzer, Martina Griesser, Katharina Uhlir, Lutz Nasdala, H. Albert Gilg, Stefanos Karampelas, and Stefan Röhrs, ’On the possibilities and limitations of provenance attribution through material analyses: New insights on the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire’, Conservar Património (2025) (forthcoming)

What do we know?

Much about this crown is unusual: its octagonal shape, its decoration with its complex meaning, and its history. Despite a long research history, scholars continue to disagree about such central questions as when and where the crown was made.

Experts in history and the history of art, literature and religion have focused on the crown and published theories about its shape, its decoration, its symbolism, and/or its use and history. However, only little of this can currently be considered completely certain and undisputed.

The following focuses mainly on basic information about the Imperial Crown. It describes its appearance, its individual parts and components, and provides general explanations for the interested public that are based on the current state of research but do not attempt to represent its breadth and depth. One measure of the success of this project examining the Imperial Crown will be the number of necessary corrections and additions to these overview texts.

Indeed, there are many instances where the information summed up here at the start of the project do require correction and expansion. In the following, this was only possible where facts and numbers were affected. The full scope of new observations, considerations, and insights requires such careful discussion and processing as is only feasible to present within the scope of print and digital publications to make it accessible for further research. The section on ’Content & Symbolism’ was kept for this overview despite the fact that historians have registered quite fundamental doubts regarding the established interpretations in this respect.

Form & Shape

Form and shape of the Imperial Crown are unlike those of any of the other extant mediaeval European crowns. But other crowns with hinged plates must have existed because a Roman icon from the early eighth century records an early example, showing the Virgin wearing just such a crown.

The Imperial Crown is 24.77 cm tall (height of the front plate including the frontal cross) and comprises three elements that date from different periods.

Eight large plates form the circlet, with plates encrusted with precious stones alternating with pictorial plates. Empty mounting tubes on the inside walls or along the bottom edge of some of the plates are all that remains of additional now-lost decorative elements. Small sleeves on the inside walls of the front and back plates were presumably already reused in the eleventh century to attach the extant arch. The cross surmounting the front plate is a later addition, too.

Scholars still dispute the dating of the crown’s various elements. Art history has dated the circlet by its decorative elements to around 980 BCE; historians, by contrast, find on the basis of the inscriptions on the enamel panels that the circlet cannot have come into existence earlier than the second half of the eleventh century. Current technological and material-analysis examinations have clearly shown that the inscriptions were not added to the enamel panels at a later date. Corresponding to the different approaches to dating the crown, the name on the arch is also assigned variously to either Conrad II (r. 1024–1039) or Conrad III (r. 1138–1152). The frontal cross has hitherto been dated to the late reign of Emperor Henry II (r. 1002–1024), largely on the basis of art historical reasoning.

The Circlet

Its eight large plates are joined together by hinges with pins. This means it was originally easy to dismantle the circlet, though the construction remained somewhat unstable until the addition at some later date of two reinforcing strips of iron riveted to the inside walls of the circlet.

The arched plates are between 11.8 and 14.9 cm tall, which means they differ both in height and decoration.

The main plates over forehead, back, and temples are set solely with precious stones and pearls, while the alternating smaller plates also feature depictions executed in cloisonné enamel. Small, now-empty gold tubes once held ornaments fashioned from precious stones or pearls. Decorative bands or pendant chains were presumably once suspended from the eyelets on the lower edges of the two side plates. All plates are clearly designed to enhance the brilliance and luminosity of the gemstones: hence the openwork below their complex raised mounts.

The Arch

The removable arch is attached to the crown with thorn-like pins inserted into tapered sleeves on the inside walls of the front and back plates. We may assume that it, too, originally helped to reinforce the unstable circlet.

Its exceptional shape is dominated by eight arches decorated with both a frame and an inscription executed in seed pearls. The latter runs over both sides of the arch and reads: ’CHVONRADUS DEI GRATIA/ROMANORV (M) IMPERATOR AVG(VSTVS)’ (Conrad by the grace of God/august Emperor of the Romans).

It is generally assumed to refer to Emperor Conrad II (r. 1024-1039). More recently however, some scholars have suggested Conrad III (r. 1138-1152) instead, although he was never crowned emperor.

The decorative details and the stones’ simple settings are very different from those used on the circlet. This and the way they are mounted suggests arch and circlet were not produced at the same time.

A central fracture and repair from an unknown point in time resulted in a shortening of the arch from a length of originally 23.1 cm to 21.75 cm. This is probably connected to the insertion of the two iron strips that not only set the originally flexible circlet into a (fairly) regular octagon, but also defined the current distance between the front and neck plates into which the arch would not have fitted in its original length.

The Central Cross

The front plate is surmounted by a cross that is 9.9 cm tall (13.75 cm with the pin); its front, too, is set with precious stones and pearls. There is, however, no openwork and both settings and decoration also differ from those found on the circlet or the arch. The reverse is decorated with an engraved depiction of the crucified Christ, an image rarely used during the early and high Middle Ages. The early and high Middle Ages focused instead on depicting Christ’s victory and triumph over death, generally symbolized by gemstones and pearls – the decoration used on the front of the cross.

Style and handling of the depiction of Christ on the reverse are similar to those found on a number of goldsmith works produced around 1020. The cross was a later addition to the circlet and its mounting is surprisingly improvised. The pin of the cross is plugged into a sleeve that is inserted behind the top, heart-shaped sapphire. It is held in place with a prong that was soldered onto the sleeve and had originally been a part of the precious stone’s mount.

The Velvet Cap

Inside the circlet is a red velvet biretta dating from the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Both a drawing of the Imperial Crown by Albrecht Durer and his ideal portrait of Emperor Charlemagne painted around 1510 show that such caps existed much earlier. Rows of holes along the bottom edge of the plates and fibre remnants attached therein indicate an earlier stitched connection between the velvet biretta and the circlet.

The crown was very large, measuring a distance of 22.9 cm between the plates over the temples, and also very heavy with a weight of around 3.5 kg.

It is highly likely that the biretta served first and foremost to offer support and padding on the head of the person wearing the crown during coronation celebrations or other events at which the crown was used.

Extant records from the early modern era tell us that newly-elected rulers had fittings prior to their coronations and that the mediaeval robes were adapted and altered in an attempt to make them fit the newly-elected ruler as best as possible. This also included fittings for the crown; small sewn-in pads allowed for alterations of the size of the velvet cap, some of which have survived in the extant cap.

Material & Technique

The total weight of the Imperial Crown in its current condition is 3,465 grams. All metal elements are made of high-carat gold. A special feature is the chased openwork in the base plates above which there are precious stones and pearls in their raised mounts. In addition to these mounts, the base plates feature intricate ornaments of filigree wire and granule pyramids. Only the strips that were riveted to the insides of the plates at a later date in order to stabilize the circlet are made of iron. The eight plates were originally embellished with altogether 144 pearls (plus eight pearls on the hinge pins) as well as 181 precious stones, all carefully selected and arranged by colour, shape, and size.